Mālō e Lelei, the Tongans say in greeting, as we focus on their village and activities in our November 2014 e-newsletter. Tongan culture is still very much alive, not only here at the Polynesian Cultural Center, but back home in the South Pacific and among our people who have emulated their seafaring ancestors by migrating to Australia, New Zealand, Hawaii, and various parts of the mainland U.S. in more recent years.

Mālō e Lelei, the Tongans say in greeting, as we focus on their village and activities in our November 2014 e-newsletter. Tongan culture is still very much alive, not only here at the Polynesian Cultural Center, but back home in the South Pacific and among our people who have emulated their seafaring ancestors by migrating to Australia, New Zealand, Hawaii, and various parts of the mainland U.S. in more recent years.

You’ll find a disproportionate number of them also represented on college and professional football teams, as well as in Australian football and professional rugby leagues.

PCC’s Tongan Village: A noble heritage

We want to focus on a couple of things that make our Tongan Village very unique:

We want to focus on a couple of things that make our Tongan Village very unique:

The first is PCC Tongan Islands manager Tevita Alamoti “Moti” Taumoepeau, who is carrying on a tradition of serving as “village chief,” the same position previously held by his late grandfather, also named Tevita Alamoti Taumoepeau, and his late father, Viliami ‘Unga Afuha’amango “Afu” Taumoepeau.

“To be a part of that legacy as the current manager fills me with a whole lot of emotions,” the youngest Taumoepeau said. “I don’t think there’s anyone else currently here at PCC who can make a similar claim. To follow in their footsteps was always a dream of mine.”

Taumoepeau explained that his family name — which literally means

“fights with waves” —“was given to an ancestor of mine who was a navigator for the king and royal family. On one particular voyage, he was ordered to take the queen to the Ha’apai group of islands, but as they were out on the ocean, a huge storm struck and the canoe began to break apart. He came forward with a spear, stabbed the hama [outrigger] and held it together while he finished guiding the canoe to safety. When the king heard what he had done, he gave him the title, Fights with Waves — Taumoepeau.”

Indeed, Taumoepeau is not only proud of his legacy, but also the heritage of Tongan culture he and his fellow villagers get to share. “For those who look beyond the entertainment and activities, they will find many Tongan principles and values in our buildings and lifestyles.”

The Fale Fakatu’i …or Queen’s Summer Palace, the focal point of the PCC’s Tongan Village, “is a scale model of Anamatangi, which still stands in the village of Folaha, in a place called Kauvai, on the island of Tongatapu. It’s about a 30-minute drive from the capital of Nuku’alofa. That was one of the places Queen Sālote would go to seclude herself and write her poetry.”

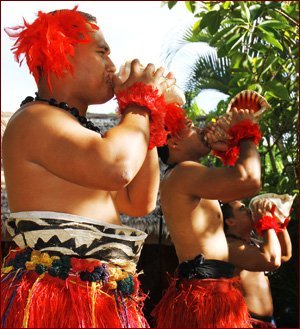

Chief Tamoepeau with Tongan villagers at the Polynesian Cultural Center

He explained that HRH Queen Sālote Tupou III, sent two master craftsmen to build the replica as one of the original Polynesian Cultural Center buildings in 1963. “Today, it’s officially recognized by the Tongan government as a building where we can conduct official ceremonies.” He added that while the popular Queen Sālote passed away in 1965 before personally visiting her summer palace in Laie, her son King Tupou IV, grandson Tupou V and other members of the Tongan royal family have since visited it, as recently as earlier this year.

“The last remaining kingdom”

That seems fitting for a group of islands sometimes referred to as the last remaining kingdom in the South Pacific: “But today, we’re actually a constitutional monarchy,” Taumoepeau said. “Tupou VI is presently our king, and we’re awaiting his coronation next July. He visited Laie as a young prince, but he didn’t come into our village at that time.” “King Tupou V instituted a number of democratic reforms before he passed away about three years ago, but our people still respect and revere our royalty to this day. Our modern Legislative Assembly, a parliamentary-style of government, is comprised of representatives from the people and royalty, roughly similar to the UK House of Commons and House of Lords.”

Making ngatu or bark cloth

As Taumoepeau explained this, he was sitting in front of the Queen’s palace, with a 25-yard-long piece of tapa or bark cloth, which the Tongans call ngatu, stretched out in front. “Making ngatu is still very much a part of Tongan culture,” he continued, estimating it would take a group of women five or six months to complete a piece as large as the one laid out that afternoon in the Tongan Village. “This is actually a modest-sized piece of ngatu,” he continued. “I’ve seen ones that are about 100 yards long.” Pretty amazing when one realizes that the bark comes off the spindly hiapo plant at approximately 2-3 inches wide and 5-6 feet long.

The women soak these strips, and then pound them with wooden mallets against a log anvil, expand them into thin, creamy colored pieces about a foot wide. Many of these are then overlaid and glued together to create larger ngatu. Taumoepeau said PCC satisfaction surveys show that “visitors find our village demonstration on making bark cloth fascinating.” “Today ngatu is mostly used as gifts. It’s customary whenever two parties get together to exchange gifts, including ngatu and fine mats. The more important the recipients or the more they love them, the longer the piece.” “Centuries ago, however, it was mostly used for clothing, and wrapped around the waist on special occasions. It was used as a shroud when people died, because we didn’t have coffins back then. It is sometimes used as bedding, piled deep like a mattress and also like a blanket when it gets cold.”

The Drumming Show

Visitors to the PCC’s Tongan Village also discover a delightful blend of traditional and comic entertainment. “We’re just as fun-loving and happy as the other Polynesians, when it comes to showcasing our music and dancing,” Taumoepeau said.

“Our tā nafa or drumming show is a very fun activity, and it’s also very cultural. For example, some of the drumming beats are symbolic of pounding ngatu and other portrayals of daily lives.”

“Everyone also listens to the sounds of traditional seashell trumpets and the fangufangu — a nose flute traditionally used to gently wake the king.

Next, we teach everyone the synchronized motions of a simple Tongan mā’ulu’ulu or sitting dance.”

But the full-on fun begins when the emcee selects volunteers from the audience, each of whom gets a hilarious lesson on how to be a Tongan drummer. You have to see it, again and again.

As the show lets out and the visitors move on to the other Polynesian Cultural Center villages, Taumoepeau shares a last thought:

“I want to pay tribute to those who were here before us — not only my grandfather and father, but those who laid the foundation of what the Tongan Village is today.”

“Without their contributions, we wouldn’t be where we’re at now. I hope to continue that legacy and uphold the principles and values of Tongan culture. I’m very grateful to be a part of this legacy.”

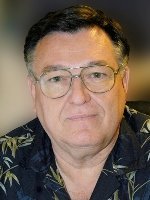

Taumoepeau’s grandfather, shown here in 1993, was a widely respected Tongan composer, choreographer and poet. — photos by Mike Foley

A Tongan pronunciation primer

For some reason, a lot of people struggle with the correct pronunciation of the word Tonga: It’s the “o” and “ng” sounds that trip up a lot of tongues, which is surprising because these phonetic components of the word are common in spoken English.The first syllable is pronounced just like the English word toe — you know, those things on your feet. Remember, toe (rhymes with low or Joe), not taw (rhymes with jaw or law). Now the harder part: The ng sound in Tongan is pronounced just like the same two letters in the English word singer, and not as in the English word finger. In phonics we call the first ng example an eng or unreleased-G, and the second an ung-guh with a hard-G or released-G sound. Just as we don’t say sing-ger in English, there are no hard-Gs in any Tongan word. Ever. Period. So, the correct pronunciation is more like TOE-nguh, with the accent on the first syllable.

BTW, this pronunciation guideline also applies to Maori and Samoan, but note that Samoan spelling only uses the letter-G (not NG as in Tongan and Maori) to represent the unreleased-G sound. For example, Tongans write the name of their islands as Tonga, while Samoans would traditionally write it as Toga, and both would pronounce it identically.

Remember, think singer, not finger. Got it?

Story by Mike Foley

Mike Foley, who has worked off-and-onat the Polynesian Cultural Center since1968, has been a full-time freelancewriter and digital media specialist since2002, and had a long career in marketingcommunications and PR before that. Helearned to speak fluent Samoan as aMormon missionary before moving to Laiein 1967 — still does, and he has traveledextensively over the years throughoutPolynesia and other Pacific islands. Foleyis mostly retired now, but continues tocontribute to various PCC and other media.

Mike Foley, who has worked off-and-onat the Polynesian Cultural Center since1968, has been a full-time freelancewriter and digital media specialist since2002, and had a long career in marketingcommunications and PR before that. Helearned to speak fluent Samoan as aMormon missionary before moving to Laiein 1967 — still does, and he has traveledextensively over the years throughoutPolynesia and other Pacific islands. Foleyis mostly retired now, but continues tocontribute to various PCC and other media.

Recent Comments