Lono Logan

The air smells of earthiness: the scent of green growing things mingles with the mustiness of a loʻi, the wetland ecosystem in which many varieties of kalo grow. A mahiʻai kalo (kalo farmer) and his haumāna (student) patiently tend the plants, treading the bog-like beds purposely, harvesting the sections that are ready, tending those that are still maturing, treading unused plant parts into the muddy bottom, and encouraging the fallow loʻi section in the process of decay and regeneration. This is what one sees; but the reality of the depth of this operation extends back generations, to the ancestors who depended on kalo plants for their very existence.

Lono Logan is a native of Lāʻie. He spent a lot of time in his early years on the grounds of the Polynesian Cultural Center with his grandparents, Jubilee and Eugenia Logan. They were among the people who helped build the center, then worked in many areas helping guests experience their Hawaiian culture. As a young adult, Lono served as a missionary for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Arizona, then came home surfed and worked at different jobs before literally returning to his ʻāina (land). He became the keeper of the kalo plants at the Center in 2017.

Lono had the great fortune to learn many nuances of growing and using kalo from two mentors: his grandmother, and his kumu (teacher) “Uncle” Jerry Konanui.

The Beginning

Lono’s grandparents were fixtures at the Polynesian Cultural Center. When Lono was a young child, his grandmother often took care of him while she went about her work. He remembers at the age of three having her call him to help her at the poi table. She put his hands on the pōhaku kuʻi ʻai (stone pestle used to mash the kalo), then reached around him from behind and put her hands over his. He remembers how it felt to pound the corm, being guided by her strong, loving hands. Something about that incident planted itself deep inside him. Many years later, when he came to the Center to care for the kalo, he could feel her with him.

Later, the renowned mahiʻai kalo Jerry Konanui taught him more about how to read the plants and understand what they need. Lono learned from “Uncle Jerry” the methods that mahiʻai have developed over eight generations. Those have become part of his being, and Lono finds great satisfaction in the service he offers the ʻāina and the people in raising kalo. As he describes the plants and the ʻāina, it is obvious that he regards them all with as much reverence as he has for humans. In fact, during the interviews that led to this article, it became clear that Lono’s philosophy of life and his understanding of how to care for kalo are entirely intertwined. For him, the link between man and nature is deep; he sees parallels between what is needed for plants and for people to flourish.

Kalo Origin

“Kalo is the fabric of Hawaii,” Lono said; he related the kalo history that has lived for centuries—the story of how kalo and the first Hawaiian came to be.

In the beginning, the Sky Father and the Sky Mother had a daughter. The daughter had a son who was stillborn. They buried him, and the daughter’s tears watered his grave often. The first kalo plant began to grow from the grave, and they named it Hāloanakalaukapalili, feeling that it was the living essence of the deceased child. (They shortened the name to “Hāloa” for common use, but later that was changed to “Kalo.”) The daughter had another son, and fed him from the root of the kalo plant, so they named him Hāloa, too, to honor his elder brother. He grew strong and healthy, and became the first Hawaiian. Hāloa cared for his elder brother (Kalo) and Kalo cared for his younger brother and his family. This was the beginning of a deep spiritual connection of the people to the ʻāina—a literal brotherhood.

Kalo’s Significance in Hawaiʻi

Because kalo was the mainstay of everyone’s diet in these remote islands, the mahiʻai had a serious responsibility to be sure to bring in the best crops possible on an ongoing schedule. They needed to know exactly what conditions the plants needed and when they would be ready to harvest. They also needed to know how to restart new growth on existing plants to speed the next round of food gathering. The success of the kalo fields was often a life-and-death scenario. To pass on their knowledge, the mahiʻai developed stories and chants to illustrate how processes worked. This helped their students both remember methods and have respect for the work they were doing.

The Kalo Plant

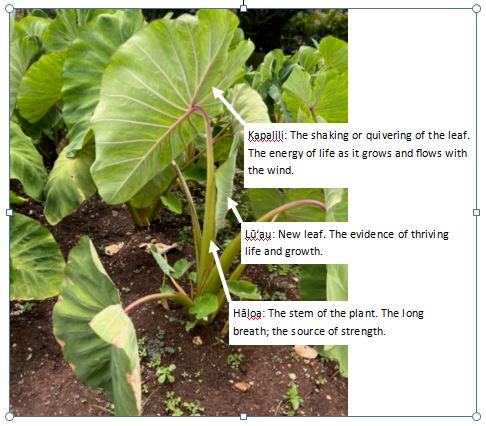

Parts of the kalo plant.

There are dozens of points of anatomy that a mahiʻai could explain; right now we will only name the basic parts of the kalo plant. You may notice that each of the names reflects pieces of the name of that stillborn son who originated the kalo plant, Hāloanakalaukapaliili.

Hāloa —Stem of plant—The long breath, the source of strength.

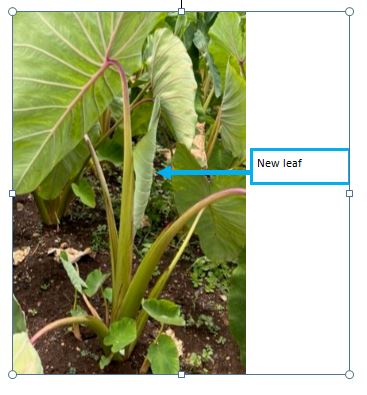

Lūʻau—A new shoot or new leaf. The evidence of thriving life and growth.

Kapalili—The shaking or quivering of a leaf as it grows and as it flows with the wind; the energy of life keeping it reaching upward. (Some Polynesian dances include shaking hands, which represents this kind of energy—for plants and for people.)

There have been well over 200 varieties of kalo identified, but not all varieties are grown on Oʻahu. They all have different properties; however, each one is strong and can stand firm against the hardships that surround it, if given the support it needs. This is very much like people. Each is unique, with different needs and experiences. To help that person develop, those who care for her/him should understand what that person requires for optimum growth.

For the unschooled, it is difficult to distinguish the subtle differences that separate each plant variety, but families are a bit easier to see: variations include dark purple; light, bright green; green with yellow veining; dark green with purple on the stem; and the list goes on.

Growing Kalo

Kalo plants grow in soil, next to the loʻi (wetland bed), the edge of which is on the right.

As the mahiʻai treats the kalo and the ʻāina with respect, the kalo responds in kind. As anyone who has grown plants knows, they respond to the treatment they are given (which, Lono pointed out, is also true of people as well). Mālama (caring, nurturing) leads to growth. Pilina (making a connection and building a relationship) allows it to flourish. The kalo has to trust that the mahiʻai will care for it, even in bad circumstances—much like people learn to trust ethical people, or God.

The varieties of kalo are organized into families, yet each is individual and responds to its environment in different ways. The key to healthy growth is putting each plant in the place where it will flourish. Some prefer fresh water beds, similar to those where rice is grown. Some do well by the sea. Still others do better in drier places—some in rich garden soil and some in dirt with different nutrients. Each one has its preference, just as each person is an individual with unique requirements. A good mahiʻai responds to quiet signals from the plants and learns what each needs.

Hands-on Training

Students learn to harvest kalo from the loʻi properly.

During an early morning training session for student workers in the Polynesian Cultural Center’s Island of Hawaiʻi, Lono taught by example and explanation, but more from hands-on participation. They were at the kalo field in the center of the village, just in front of the hale hana, where workers demonstrate how to make poi. [Poi is the Hawaiian staple food made by mashing the corm (root) of the kalo plant.] Much of the kalo at this location is grown in a loʻi kalo, which is a wetland ecosystem. Each of the four loʻi sections are lined with rock and filled with about 12 inches of thick lepo, a nutrient-rich mud, with a few inches of water above that. This medium takes years to develop, as it builds naturally upon decomposing plant parts that are stripped off the kalo in the harvesting process. It is so valued that every bit that adheres to feet, hands, and harvested plants is washed back into the loʻi to prevent loss. Small fish and other organisms also live in the loʻi system, enriching the environment.

The mahiʻai likens this to what it takes for the character of a person to develop. It’s a process that takes years—even a lifetime. The fertile ground that allows someone to grow in strength is built upon the experiences in that person’s life. The mind learns from those experiences; then knowledge breeds wisdom. All that feeds the soul.

The Wetland Loʻi

One section of the loʻi.

The Polynesian Cultural Center’s wetland ecosystem is built on a slight slope, carefully engineered to deliver water to all four sections in the requisite amounts—not flooding, and not starving the plants. Kalo is very aware of changes in water level, so this is an important factor. A basic dam also helps control flow, as do plants on the water’s edge. The plants along the bank also contribute to filtration and aeration.

One section of the loʻi had recently been harvested, to serve as food for the crew of Iosepa on their voyage. A student invited to walk through the “empty” space there helped us learn that much was happening below the surface. At this early stage, organisms in the mud were busy breaking down the stripped-off parts of the plants, creating a wealth of nutrients, and a lot of methane gas. Replanting that section will be timed by the dissipation of the gas, which will decrease as the plant material is assimilated into the soil.

As for people, don’t we also take the difficult things in our lives and deal with them, “digest” what we’ve learned, and apply that wisdom to nourish ourselves for the future?

It’s incredible that kalo is at once so sensitive and so resilient. While it can detect what might seem to humans to be subtle changes in environment, it can also adapt quickly to ensure its own survival in an assortment of circumstances. The result of that ability was illustrated by the fact that around the perimeter of the loʻi there were other varieties of kalo that were thriving in soil, receiving water only from rain and the care of the mahiʻai.

Sensitivity is also evident in the handling of all the kalo plants. Lono made it very clear that if anyone who planned to enter the loʻi to help with harvest should not step into it if she/he was experiencing negative thoughts or emotions. In the loʻi, the workers faced each plant they were working on, showing it respect and passing along positive energy. Likewise, humans will find that they have more productive encounters with others when they show respect and project positive attitudes.

A plant being harvested was coaxed gently out of the mud, and roots and leaves not to be used were stripped off and pushed back into the growing medium, renewing the life cycle. Two lessons here: First, everyone and everything has a purpose. Sometimes it is our responsibility to help identify their purposes and gently nudge them toward fulfillment. Secondly, no purpose is beneath the dignity of any other. Every role is important to the whole.

Raf Adolpho, a student learning to care for kalo, strips off parts of the plant, putting them back into the microbiome to perform their next functions.

Sustainable Propagation

Lono shows a student how to cut the kalo.

Once out of the ground, the plants are thoroughly rinsed, putting all that nutrient-laden lepo back into the loʻi. Lono taught how to prepare the kalo—both for eating and for replanting.

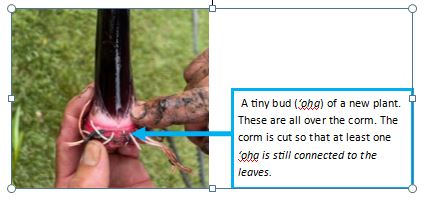

An interesting fact to consider at this point is that kalo plant structure is the “root” of the structure of Hawaiian culture. When harvested, the corm is covered with roots, which are stripped off. Also growing from the corm are buds of new plants. Some are already developing and growing leaves. One bud is called an ʻoha. Multiple buds are called ʻohana, Hawaiian for “family.” This is how a strong family develops: one central, governing part that nourishes and encourages new fledgling parts.

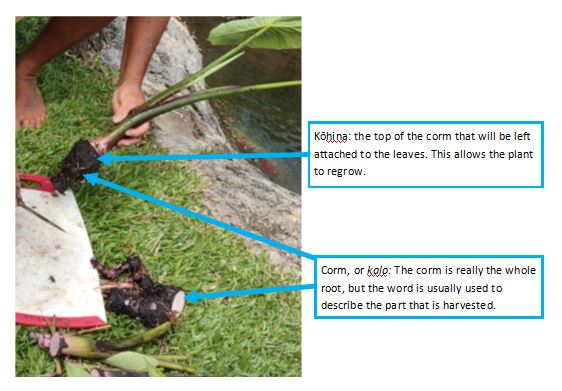

When the corm is harvested, it is cut so that at least one ʻoha (bud) is left at the base, and enough of the root to hold the leaves together (about ¼“ below the collar of the root). This piece is called the kōhina.

Harvesting part of the corm for eating.

The largest part of the root, below the kōhina, is called the “corm,” though often it is just called the kalo, since this is the part most people are familiar with. This is what is harvested for eating. At this point it can be a little easier to tell the difference in varieties by the color of the flesh of the corm—but only a little. Remember, the plants are grouped in families, and families have similarities. We tend to think of poi as purple, but some kalo have white or beige flesh. Leaf and stem color are also helpful in determining the family the plant belongs to. This helps in deciding how to prepare it as food. For instance, some varieties require much longer cooking that others. Knowing which type you’re working with is very important to providing a safe, palatable meal. (Some kalo—and specifically some parts of some kalo plants—are nourishing food if properly prepared; but if not properly prepared they can trigger allergic reactions.)

Kalo corm, ready to be pounded into poi.

Poi is made by first steaming the corm to help remove the outer skin, then cooking the corm, similar to cooking potatoes. The cooked kalo is then mashed with the pōhaku kuʻi ʻai (stone pestle) to make paʻi ʻai, which has a thick consistency. Adding water allows the paʻi ʻai to be thinned until it becomes the smooth paste known as poi. More water can be added as needed to get the desired consistency.

How to use the pōkau kuʻiʻai (pestle stone) to work the corm.

Poi that has been prepared for sampling at the Polynesian Cultural Center’s Island of Hawaiʻi Village.

Fresh poi has a mild taste and is rich in vitamins and fiber, making it a valuable staple in the Hawaiian diet. (Some people enjoy fermented poi, but that is another topic.)

There are other foods that have kalo as their bases. A delicious recent development is using the corm to make taro chips. Kūlolo is a dessert made of flesh of the corm, sugar and coconut milk, wrapped in ti leaves.

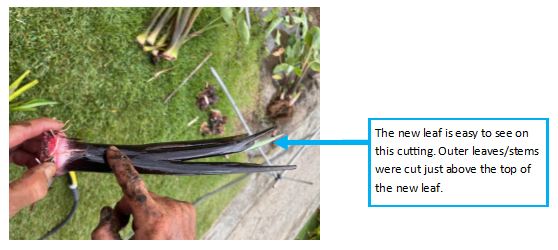

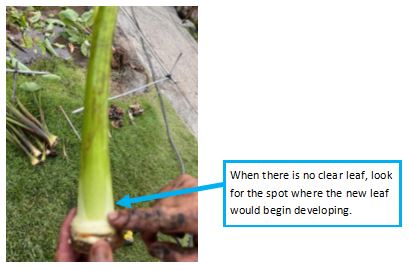

Preparing the Huli

The top of the plant must be prepared for replanting. This speeds the growing cycle, ensuring that there will be food again soon. Old outer leaves are stripped off until there are only three—and sometimes two—left. This is called a huli. If there is a lūʻau (new leaf) starting to emerge, that is gauge by which cuts are made. The hāloa (long stalks) are cut just above the top of the new lūʻau. If there is no lūʻau, the preparer must look carefully at the structure of the innermost stem, and find the spot where a lūʻau would likely be forming. The cut is made above that spot.

When there is a new leaf evident, the other stems are cut just above the level of that leaf.

Once the huli is prepared, Lono’s crew place a shallow cut across the end of each kōhina to show which generation of the plant this is. Old markings on the bottoms of the harvested corms are the guides. If the corm is unmarked, it is first generation. This new cutting receives one shallow slash across the bottom. If the harvest corm has one mark on it, the huli gets an “X” (two marks). If the harvested corm has an “X,” this one gets three slashes. Three replantings is the limit for most kalo. After that, there is not enough energy left to produce a robust plant.

The marking on the end of this corm shows that this is the second generation of this plant.

Other Parts Eaten

Leaves can be eaten when they are carefully prepared. Leaves that are too old carry a lot of allergens that can cause throat irritation, and in some people, allergic reaction. (They are also tough and not easy to eat.) Young, tender leaves can be thoroughly boiled until allergens are broken down. Young, tender stems can also be cut up and cooked in coconut milk.

Other Uses for Kalo

Kalo can be a powerful medicine. Poi contains probiotics, which help settle and strengthen the digestive tract. Kalo stems can treat insect bites, stop bleeding, and treat infections. The stems can also be used to dye kapa (bark cloth), and thinned poi can be used to glue pieces of kapa together.[i] Though lesser known, these roles of kalo demonstrate how fundamental it has been to many important aspects of island life.

The Wisdom of the Mahiʻai Applies to All Life

Lono Logan

Lono’s knowledge is powerful—and not only for the continued success of traditional kalo farming. Remember that he values the ʻāina (land) and the kalo as much as he does people. He understands that much of what it takes to help kalo to be happy and healthy also applies to us two-legged creatures. If we live in good conditions, where we receive physical and spiritual nourishment—we will flourish fairly easily. If we are placed in cold, negative, less hospitable places, we will grow more slowly, but we can still grow. We will adapt, and will become more resilient because of the struggle.

Viewed from the perspective of a mahiʻai like Lono, kalo offers food for thought as much as nourishment for the body.

[i] Kalo in Hawaiian Culture. Hawaiʻi ‘Ulu Cooperative. Accessed 11 July 2025.

Recent Comments