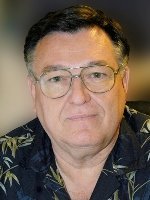

Doug Christy, a 37-year veteran Maori wood carver for the Polynesian Cultural Center (PCC) in Laie, Hawaii, learned his craft from his father, who also worked at the PCC for many years. Now he and the other senior carvers at the Center teach those same skills to a new generation of student workers.

Christy explained that before hiring any of them, the department manager and senior carvers usually meet first with new student worker applicants to determine if they have the potential to learn carving.

One thing stood out to Christy. He said, “For the first time, he noticed we had so many applicants from different places. One girl was a Filipina from Japan. We hired a young man from Hong Kong. We have two Tahitians who are working with us and two Maori boys, but one of them is part-Samoan who spent time as a Latter-day Saint missionary in Fiji. So among them, they cover a lot of languages and bases.”

Tools of the trade

Similar to how culinary students carry a rolled-up set of knives, Christy unrolled a student worker carving set. He explained that wood carving tools can come in hundreds of various sizes and widths — from micro to immense, but PCC student workers start with a set of about 12 chisels and a wooden mallet.

Hobbyists can find similar, relatively inexpensive wood-carving sets online, but at the PCC each fine-steel chisel in the carving kits costs about $40, and they are divided among five or six styles.

A Polynesian Cultural Center woodcarving chisel kit.

A set includes:

♦ Gouges are half-round chisels with vary degrees of roundness, all the way from “half-moon” to nearly flat.

♦ Veiners, or v-chisels, can be leaned to either side to create scallops and shaped cuts.

♦ A skew is a straight-edge blade on an angle.

♦ A flash is used to make smooth and straighten cuts.

♦ A spoon chisel: Used to “get a little lower.”

♦ Wooden mallets come in various shapes. “That’s really a matter of personal preference,” Christy said, noting that some carvers use rhythm of the tapping to pace their work.

“It turns out that smoother lines usually result from faster taps that drive the chisel ahead in shorter increments,” he said. “One of my student workers sounds like a woodpecker.”

♦ Chain saws: Polynesians have always been innovative when it comes to using the materials and tools at hand, and some carvers like using chain saws of varying sizes to rough-shape their creations.

The ancient toki or adze

Depending on the project and scale, some carvers prefer to use adzes, or toki, which was the heavy-duty Polynesian carving tool of choice for centuries. Some still use it, although some woodworkers today never use an adze, a cutting tool like an axe but with an edge running perpendicular to the handle.

A Maori toki (adze) with a greenstone blade.

Traditional Maori carving is usually said to have reached the highest level of detail in the islands, partially because they had access to pounamu — Maori greenstone they used for their toki blades that could hold a finer edge.

“But it wasn’t just the pounamu,” Christy said. “Our ancestors also had access to many different types of wood in New Zealand. For example, we made weaponry from ironwood, or waka (canoes) from toutara and kauri.

Whether a chisel or an adze, Christy added that sharpening each blade is a “whole different ball game” that may include using table grinders “for edging and shaping,” oil stones, water stones, and whet stones (for final edges).

Christy added he’s created a sharpening jig, which helps him sharpen a chisel in about five-to-seven minutes, whereas other people may take a half-hour per blade.

Starting carving projects

Doug Christy uses a wooden mallet to “tap-tap-tap” the back of a woodcarving chisel.

“Once we’ve got the concept in mind, then we gather the materials, depending on whether it’s a PCC work project or private commission,” Christy continued. “We like to get things for the Center done rather quickly.”

Next, fit the concept or design to the piece of wood by drawing the design, tracing a pattern template, snapping a chalk line or all of the above. “If you’re shaping something out of a piece of wood, you’re going to be lowering everything but the design down. We would first use one of the v-chisels to outline the shape.”

In the early stages of training, Christy and the other carvers supervise the student-workers closely. “We like clean lines. If they do it wrong, then I have a lot of clean-up to do. Consequently, I have them do a lot of design work first. Of course, they begin with simpler projects.”

Sharing the experience with our guests

Polynesian Cultural Center visitors get to watch some of this happening in the Maori Village in back of the meeting house, but the clever carvers have also devised an activity for everyone to try to give them a “taste” of making their own creation.

Guests push sculpting clay through a jig in the shape of a traditional fish hook, and then they decorate it. “We bake each of them for about five minutes, tie a neck cord around it, and the guests love it. We see these finished ‘carvings’ all over the Center.”

Your children can create their own “huki” necklace in the Carvers Hut.

Not just decorations

“Traditional carvings are not just decorations,” Christy stressed. “There’s history and genealogy behind many of our designs. They’re also almost like time capsules in various islands.

“I’m very particular with my own work. For example, I had a student who was doing a design that wasn’t right, so I erased it. His feelings were hurt and said he was going to quit; but I asked him, do you want to know how to stay true to the culture, or do it your own way? In the end, he agreed he wanted to learn to do things the right way, and later wrote me a letter thanking me for helping him see that.

“I want to instill the right knowledge of Maori carving in the student-workers. Many of them may never use these skills again beyond the Center, but a few may pick these lessons up and run with them. It’s not an easy task to learn this ancient art, so I try to do it in a loving way.”

Christy said he would also like to see more students learn how to carve at the Center. “There are many carving schools in New Zealand,” he said, “but I want PCC to be the go-to place. And not just for traditional carving: we’re also experimenting with using lasers and other modern technology.”

Story and photos by Mike Foley, who has been a full-time freelance writer and digital media specialist since 2002. Prior to then, he had a long career in marketing communications, PR, journalism and university education. The Polynesian Cultural Center has used his photos for promotional purposes since the early 1970s. Foley learned to speak fluent Samoan as a Latter-day Saint missionary before moving to Laie in 1967, and he still does. He has traveled extensively over the years throughout Polynesia, other Pacific islands and Asia. Though nearly retired now, Foley continues to contribute to PCC and other media.

Story and photos by Mike Foley, who has been a full-time freelance writer and digital media specialist since 2002. Prior to then, he had a long career in marketing communications, PR, journalism and university education. The Polynesian Cultural Center has used his photos for promotional purposes since the early 1970s. Foley learned to speak fluent Samoan as a Latter-day Saint missionary before moving to Laie in 1967, and he still does. He has traveled extensively over the years throughout Polynesia, other Pacific islands and Asia. Though nearly retired now, Foley continues to contribute to PCC and other media.

Recent Comments