“Princess Adi Cakobau.” Pinterest, https://uk.pinterest.com/pin/550002173217140279/. Accessed 28 September. 2024.

You may have noticed how the Islands of Fiji are represented throughout the Polynesian Cultural Center with an icon of a person rocking an Afro hairstyle. “Afro” is how the world knows it, but in my island home, this hairstyle is a symbol of our identity that has been passed down through generations. We call the hairdo buiniga.

HISTORY OF FIJI

There are no written records of the people of Fiji until the first voyagers arrived in Fiji. The first ever documentation of the Islands of Fiji is sighted in the journal of Abel Tasman, who is also the first known voyager to have discovered Fiji. W and Henderson’s book, Discover of the Native Islands highlights Abel Tasman’s records of how he describes his discovery of Fiji and a collection of journals of other voyagers including: James Cook, William Bligh, James Wilson and Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen. It was in Bellingshausen’s journal that the first attention was paid to the details of how Fijians wear their hair. Bellingshausen discovered the islands of Ono-i-lau in the 1820. Here is an account of how he describes Fijians.

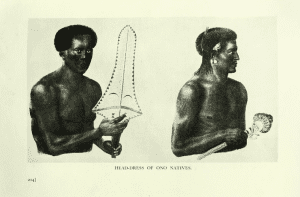

W, J. A., and G. C. Henderson. “Head-dress of Ono Natives”, Feb. 1934, p. 224. https://doi.org/10.2307/1786470.

“His hair has some gray hairs and is carefully dressed like a wig.”

They dress their heads very carefully in the following way: all the hair is divided into tuffs which are bound at the room [root?] with a thin thread: then they comb their [the?] ends of these tuffs with care, and then their heads are like wigs. Some islanders apply a yellow pigment to their hair; with others the front hair was only combed so, with the back hair and side curl hung twisted into small curls. Many of them had waxed combs made of strong wood and tortoise-shell hairpins a foot long which were fixed into the hair from one side horizontally. The hairpin is used by islanders when they dress their heads so as not to rumple the beautiful dressing of their hair. For the same reason the Fijians slept with the neck (not the head) resting on a wooden pillow”(p. 224).

ULUMATE or WIG

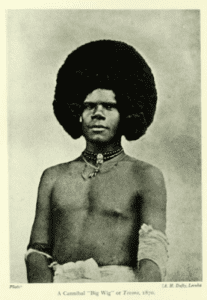

There was a time in history when wigs were a symbol of status and fashion in English society, reflecting class and prestige. In a similar way, Fijians had their obsession for wigs, mostly among the chiefly families. A book titled The Cannibal Islands or Fiji and Its People, highlights sentiments of missionaries about Fijians and their hair.

“We wonder at the ladies of former times, who on grand gala-days submitted with patience to the tedious operation of having their hair dressed in imitation of baskets of fruit and flowers. We laugh[ed?] at the Scottish ladies who, when King George IV. visited Holyrood, were so anxious to have their heads fashionably dressed, that they yielded them to the hands of the busy barber days before the court reception. But here we find the savage Fijian undergoing the same trouble and inconvenience, not for a week or a few days, but throughout his whole life. Every chief keeps a full complement of barbers. These are persons of importance and dignity; their hands being sacredly devoted to their master’s head……. The barbers are very expert in making wigs, which defy detection, when a chief is obliged thus to supply his deficiency of hair” (p. 25).

Brewster, Adolph Brewster. “A Cannibal “Big Wig” or Tevoro, 1870”, pg.56, ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA11922531.

There were three distinctions for Fijian wigs:

- Ulumate – hair that is cut and turned to a wig.

- Ulu Cavu – a warrior’s wig, where the warrior would strip the hair of his enemy and turn it into a wig, to wear for the next battle.

- Ulu Vati – the wig from the hair of someone who has passed away (GoFij).

From the journals, it is evident that hairstyles have been an important part of Fijian distinction from the beginning. Fijian hairstyle was and is a symbol of their identity.

SACREDNESS OF THE HAIR

In the Fijian culture, the head is the most sacred part of the body. One of the most disrespectful acts is touching someone else’s head/hair without permission. History relates the 1867 arrival of a missionary who did not understand the culture. Because he touched the chief’s head without consent, he and seven of his followers were killed.

KALI, OR THE WOODEN PILLOW

In the past, Fijian pillows were not what you might expect. Our traditional headrest, called the kali, is described as “a rod of wood about an inch in diameter and a foot and a half long, raised about half a foot by two diverging pieces at each end, with the nape of the neck resting upon this” (Cartmail and Keith).

(Fijian Headrest or “Kali” with Whale Tooth Inlays’ Cut by Tongan Craftsmen. Photo by Brian McMorrow)

WESTERN INFLUENCE

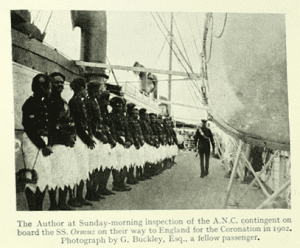

Fiji was ceded to Great Britain 1874, which marked a turning point in the country’s history. Colonial rule lasted 96 years, and impacted Fijian culture as Western customs and practices began to blend with the traditional ways of life. In terms of the hairstyle, the men moved away from the buiniga as they joined the British armed forces during World War II.

Brewster, Adolph Brewster. “On their way to England for the Coronation in 1902”, pg.208, ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA11922531.

Missionaries who came to the islands viewed the extravagant wigs and hairstyles Fijians proudly wore as symbols of paganism (GoFiji). Over time, missionary influence led to the gradual decline of these practices for most Fijians. However, the buiniga remained common among those of chiefly status, even as other traditional practices declined.

CARRYING THE LEGACY FORWARD

As I approach my 30th birthday, I reflect on how the buiniga has been part of who I am. For three decades I have carried the buiniga as an representation of my heritage and a connection to my culture. I have experimented with other hairstyles, but they have never felt right—as if I were stepping away from who I truly am. I pay tribute to my dear mother, my lifelong hairdresser, who has always called my hair my “Fijian Crown.”

Working at the Polynesian Cultural Center, I have have been approached by Fijian guests without introduction because they identified the buiniga. I remember being embraced by a guest from California, and he whispers to me, “Thank you maintaining the buiniga.” Another encounter was in town. I hear a loud, “Bula Vinaka!” from a stranger across the road. These small moments have meant the world to me—to know that a simple hairstyle signifies much more.

As Fiji’s Independence Day is October 10th. it feels fitting at this time to reflect on our heritage and the symbols that unite us. I am filled with gratitude for the rich cultural heritage that the buiniga represents. The buiniga is more than a fashion statement or hairstyle—it is a reminder of our roots and a celebration of our identity as Fijians.

References

Brewster, Adolph Brewster. “King of the Cannibal Isles : A Tale of Early Life and Adventure in the Fiji Islands.” Robert Hale Books, 1937, ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA11922531.

Cartmail, St., and Robert Keith. The art of Tonga = : Ko e ngaahi’aati’o Tonga. 1997, ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA44405488.

“Fijian Headrest or Kali With Whale Tooth Inlands Cut by Tongan Craftsmen by Brian McMorrow.” PBase, pbase.com/bmcmorrow/image/147024004.

Gifford, E. W. “Fiji and the Fijians 1835–1856. G. C. Henderson.” American Anthropologist, vol. 34, no. 3, July 1932, p. 538. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1932.34.3.02a00290.

GoFiji. “The Traditional Hairstyles of Fiji.” GoFiji, 16 June 2023, gofiji.net/the-traditional-hairstyles-of- fiji/#:~:text=From%20the%20elegant%20Dakuwaqa%20to%20the%20ornate%20Kavakava,%20explore%20the.

The Cannibal Islands or Fiji and Its People. Philadelphia, United States of America, PRESBYTERIAN PUBLICATION COMMITTEE, 1863, www.scribd.com/document/20557669/1863-The-Cannibal-Island-or-Fiji-and-Its-People#:~:text=%22The%20Cannibal%20Island;%20or%20Fiji%20and%20Its%20People.%22%20Published%20by.

W, J. A., and G. C. Henderson. “The Discoverers of the Fiji Islands. Tasman, Cook, Bligh, Wilson, Bellingshausen.” Geographical Journal, vol. 83, no. 2, Feb. 1934, p. 158. https://doi.org/10.2307/1786470.

Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Baker_(missionary).

Grace Tueli

Grace Tueli, born and raised in Fiji, is an undergraduate student at BYU–Hawaii. In her spare time, you can find her playing board games, soaking up the sun at the beach, or spending quality time with her family. Blessed with the opportunity to study abroad, Grace is passionate about sharing her Fijian culture and embracing the Polynesian Cultural Centre’s vision of “spreading aloha around the world.”

Recent Comments