Photo by Seamus Fitzgerald

October 10th was Fiji Day, which commemorates both the day in 1874 when traditional Fijian chiefs ceded their islands to Great Britain and also the same day in 1970 when Fiji regained its independence from British colonial rule.

Like many islanders, Fijians know how to have a good time, and back home the week preceding this national holiday actually becomes Fiji Week, featuring festivities, religious activities and various cultural celebrations that recognize modern Fiji’s cosmopolitan make-up.

Fijians everywhere else in the world hold local observations, including the one in the Fijian Village at the Polynesian Cultural Center in Laie, Hawaii.

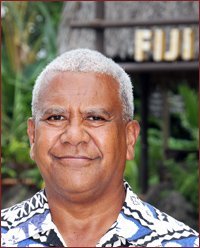

PCC Fijian Villagers actually observed their national holiday this year on Friday, October 17, “so it wouldn’t conflict with the celebrations the Fijian community planned in Honolulu and elsewhere,” said Ratu Seru Inoke Suguturaga, PCC Manager of Fiji Islands.

“When I was a youth back home, Fiji Day was always exciting,” said Ratu Seru, who has served as the PCC’s Fijian Village “chief” for the past 13 years, and is actually a hereditary Fijian chief. “It was a major holiday, and in many parts of Fiji including Suva and Levuka, the old capital, we always reenacted the deed of cession in 1874, when Ratu Cakobau ceded Fiji to Queen Victoria.”

“Our Fiji Day celebration at the PCC this year was a good opportunity for us to come together and reminisce, have some good food and a devotional. This year we also honored Nana Sereima Damuni — one of our living treasures.”

Ratu Seru explained that the octogenarian and her late husband, Emosi Damuni — a relative and also former Fijian Village “chief,” came with their young family to help start up the Polynesian Cultural Center when it first opened in 1963. “Their little children were very popular and virtually grew up at the Center,” he added. “After working in the Fijian Village for years, Nana Damuni switched over to the wardrobe department and worked backstage in the theater until she retired.”

As a titled man, Ratu Seru was involved in traditional protocol. “We still know who we are, what are roles are and what our responsibilities are. The Fijian way of life is still very much alive. The Fijians call this nai tovo vakaviti.”

“I come from a traditional chiefly family. I am a half-sibling with the Cakobau’s,” the traditional paramount chief in Fiji, “and my mother also comes from a chiefly line,” said Ratu Seru, who originally came to the Center in 1992 by way of California, where he worked in banking for eight years.

Consequently, this puts him in an excellent position to help today’s young Fijians who come to Laie to attend BYU–Hawaii and support their studies by working part-time during the school year, and fulltime during breaks, at the Polynesian Cultural Center.

“Our work-study program is designed so there’s a regular turnover of students,” Ratu Seru said. “As younger generations come to Laie, we find they are more westernized and not as well versed in traditional culture. This is not unique to Fiji, it’s true of all the South Pacific islands. A good indicator to me is how well the young people speak their own local dialects of Fijian, or not. There are over 30 dialects in Fijian; some of the students only speak common Fijian and also didn’t learn other traditional skills back home.”

“So, we have weekly training in our own culture. We take that responsibility seriously. We tell them if they do what they’re supposed to do, they will succeed. Many of them do very well. One student who spent four years in the Fijian Village, for example, went on to do an internship with the Fiji Tourism Bureau and now she covers the Asia and New Zealand markets for them.”

What’s up in the Fijian Village?

The derua beat, and more: So, when they’re not observing national holidays, Fijian Villagers at the Cultural Center are busy welcoming and entertaining guests, explaining the symbolism and significance of the chief’s house, among other activities, and teaching them how to play derua — varying lengths and diameters of bamboo that are pounded on the ground as percussion instruments to the beat of lively Fijian music.

“Our derua activity is still very popular,” Ratu Seru said. “The other thing that’s been especially popular lately is our coconut oil demonstration — watching how we make waiwai.”

He explained that many of the guests, who have already seen how coconut “milk” is traditionally made in the PCC’s Samoan Village, can now see how the Fijians further clarify the creamy-white oil, sometimes steeping it with fragrant flowers and other leaves, and turning it into a sweet-scented coconut oil.

“A lot of our guests are surprised to see how it turns out,” Ratu Seru said. “Along with many other Polynesians, we cook our food with the coconut milk, but we use the waiwai oil as a moisturizer. Many of our dancers and others traditionally rub this type of coconut oil on their bodies. It can also be used as a perfume. It’s very popular with our guests, and we now bottle and sell it.”

Finally, we point out that the Fijian Village at the Polynesian Cultural Center is the home of our very own camakau — a traditional Fijian outrigger sailing canoe.

Almost 30 years ago, about a decade after the Hawaiian sailing canoe Hokulea had rekindled major interest in traditional Polynesian voyaging canoes, the PCC commissioned master carvers on the island of Kabara in Fiji’s Lau Island archipelago (between Fiji and Tonga) to make a camakau.

Almost 30 years ago, about a decade after the Hawaiian sailing canoe Hokulea had rekindled major interest in traditional Polynesian voyaging canoes, the PCC commissioned master carvers on the island of Kabara in Fiji’s Lau Island archipelago (between Fiji and Tonga) to make a camakau.

Back then such canoes had almost passed into history, but the Kabara master carvers who had been the traditional Fijian canoe builders for centuries, still remembered the old ways.

They cut down a large vesi tree (a tropical hardwood) on May 27, 1984, and over the coming months fashioned the sleek outrigger without including any metal.

Near the end of the process, the women of the island wove a pandanus-leaf crab-claw sail. Then, after sea trials off Kabara, the beautiful craft was disassembled and shipped to Honolulu, where it was loaded onto a tractor-trailer, driven to Laie and reassembled at the Polynesian Cultural Center.

Then-prime minister of Fiji, Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara, who also held the paramount chiefly title of Tui Nayau in the Lau Islands, and his wife came to the PCC on March 24, 1986, to officially present the new camakau, which was proudly put on display.

As the years passed, Hawaii’s tropical climate took its toll on the wooden outrigger; but the sea-going canoe got new life in 2001 when the Fijian Village asked the master carvers working on BYU–Hawaii’s 56-foot twin-hulled sailing canoe if they could also overhaul the camakau. Because the logs for both canoes originated in Fiji, they agreed to also work on the “little brother” of the Iosepa.

Later that year, with several thousand people watching the launching of the Iosepa at Hukilau Beach in Laie on November 3, they also saw the camakau accompanying its maiden voyage.

“The camakau traditionally uses a step-mast that can be swiveled, so the canoe can be sailed in either direction without turning around,” Ratu Seru pointed out. “A man from Kabara once visited our village and told us that, traditionally, three or four men usually sail a camakau, but a deck can be built that includes a shelter and it can carry as many as 30 people. Just like the Iosepa, supplies can be stored in the hollow hull.”

For the past 10 years this month, the camakau is now proudly berthed in its own home in the Polynesian Cultural Center’s Fijian Village (“Big brother” Iosepa also now proudly stays in the PCC’s Hawaiian Village when it’ s not sailing, as recently noted in an earlier e-newsletter). Ratu Seru added that, starting about five years ago, building traditional camakau and racing them has gained new popularity in Fiji; “but this one is our treasure.”

Story and pictures by Mike Foley

Mike Foley, who has worked off-and-on

Mike Foley, who has worked off-and-on

at the Polynesian Cultural Center since

1968, has been a full-time freelance

writer and digital media specialist since

2002, and had a long career in marketing

communications and PR before that. He

learned to speak fluent Samoan as a

Mormon missionary before moving to Laie

in 1967 — still does, and he has traveled

extensively over the years throughout

Polynesia and other Pacific islands. Foley

is mostly retired now, but continues to

contribute to various PCC and other media.

Recent Comments