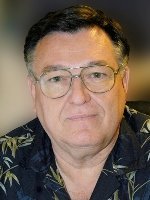

PCC Samoan cultural ambassador, knife dancer and artist Kap Te’o-Tafiti shows us his fire knife rig.

Former baton majorette looks at Samoan fire knives

A former baton-twirling majorette shared several interesting observations after watching the Polynesian Cultural Center’s recent Samoan World Fireknife Championships in May 2017.

Sister Sue Ann Long, 73, is a senior volunteer missionary from Provo, Utah, who is helping to digitize the PCC’s archives. She perfected that skill after working as an administrative assistant for the director of LDS Philanthropies (LDSP) for 13 years, and was then assigned to digitally compile LDSP’s 40-year archives. LDSP oversees charitable contributions to BYU and BYU–Hawaii.

But Sister Long has a hidden talent that helps her to appreciate the level of expertise necessary to perform with the Samoan fire knife at the Polynesian Cultural Center. Ten-year-old Sue Ann taught herself how to twirl the baton after receiving one as a Christmas gift. She eventually became the baton majorette for her junior high and high schools in China Lake, California, as well as solo twirler for the Brigham Young University marching band in Provo, Utah, in the mid-1960s.

Sister Sue Ann Long, volunteering at the Polynesian Cultural Center (left) . . . and as a BYU marching band majorette in the mid-1960s.

Adding fire to her routine

Sister Long immediately thought of her own fire baton twirling when she first visited the PCC as a tourist in 1985 and saw the Samoan fire knife dancer routines. She recalled that she added fire to her baton routine after hearing about it from other twirlers while she was still in high school.

“There were batons with lights or ribbons, but I liked the idea of fire. It looked exciting, and I wanted to go for a ‘big’ show. When you’re down on the field, it was hard to see tiny, intricate moves,” she said. “When I performed with two fire batons, the stadium lights were shut off….I loved to listen of the audience reactions when I would do my high-flying and twirling fire batons. It was thrilling”

“I twirled them through my fingers, and I would even twirl with one baton in my hand and I would put the other one between my lip and nose while twirling around.” She can still remember one rehearsal at the University of New Mexico stadium where the wind blew the one off her lip. “It burned my lip and singed my hair.”

“We used asbestos soaked in gasoline, and wrapped with aluminum foil.” (She added that using asbestos in that way is no longer considered safe).

“Of course, you have to keep the baton going so you don’t get burned, even though the fire batons didn’t have large flames like the knives,” she said. She also noted she would have been afraid of the hooks on the fire knives and getting cut. “That’s the dangerous part,” she agreed.

Samoan fire knives

Fire has been a part of Samoan knife dancing at the PCC since we opened in 1963. In fact, credit goes to the late Samoan paramount chief Letuli Olo “Freddie” Misilagi of American Samoa: He added fire to his knives in 1946 after watching a baton twirler and an East Indian fire-eater practice in San Francisco.

PCC Samoan cultural ambassador Kap Te’o-Tafiti — who is also a fire knife dancer and artist — explained, “Today, most knife dancers are very creative. Some use towels, some use particle board — all kinds of materials that will soak up gas.”

Kap Te’o-Tafiti shows how he wires particle board to his fire knife to soak up white gas on the hook end.

“At the Cultural Center we use what’s called white gas as fuel, which is clean-burning. It really doesn’t matter, but if you use unleaded gas, like for a car, it burns ‘big,’ but the fire is also dark, dirty and smoky. By the time you’re done, it’s on your skin, in your nose and throat, and the dancer is inhaling everything.”

For those interested in learning, Kap advised, “Stay close to those who know the art. Listen and learn. Start with a stick first, then advance to a knife, then add fire . . . and an audience. Finally, be careful. You can get hurt.”

Length of the knives

“Batons, of course, are much lighter in weight,” Sister Long continued. “They’re much thinner. They’re easier to handle while spinning them through your fingers and hands. They come in different lengths, depending on the length of your arm, so you’re not hitting your body all the time. When I tried to twirl one of the fire knives, it kept bumping me.”

Kap agreed. “The knife typically measures from the middle of your chest to the tip of your extended hand for one that you can comfortably dance with. If it’s longer, the knife will bump into you,” he explained.

“If it’s shorter, it’s all about composition and finding a fire knife that fits you: A big guy with short knife looks off. Remember, originally this was a weapon, so if you go with the knife you cannot handle well, then you’re going to end up getting hurt.”

Weight and bulk of the knives

“I notice the fire knives are heavier and bulkier. It’s amazing the strength the fire knife dancers have to have in their hands, wrists and arms when they’re doing a performance,” Sister Long said. “That really takes a lot of work.”

“The thickness is customized to the dancer,” Kap responded. “Most of us use a large wooden dowel for the handle, which we put into an aluminum pipe for rigidity. We then wrap the pipe with electrical tape, which gives us a little better grip, and also makes the handle easier to see in the dark.”

“Balance is key to the knife dance. The ‘ball’ on the one end has to have the same weight as what we put on the hook end.”

The basic moves

“All of the ways they spin a knife are similar to the ways I used to twirl my baton,” Sister Long said. “They may not be able to run it through their fingers as well, but they can spin and catch it. They can let go, catch it and keep it spinning. I used to be able to do that, but not as well. They do it so proficiently.”

“I noticed that their two-hand twirl is a little different than I used to do with a baton, but their fire knives are heavier. They have to spin it a certain way to keep it going, and that takes a lot of strength.”

“Besides the traditional stances and some of the moves”, Kap added, “the basic movement is holding the knife in your right hand with the palm down and spinning your wrist clockwise until the knife is on top of the right thumb. Just before the knife falls off your thumb, as the momentum keeps it spinning, you catch it with your left hand, palm up. Your left-hand gives the knife a half-turn clockwise, and your right hand comes back to grab it, palm down, and repeats the movement,”

“Most knife dancers start with this full-circle move, getting the fire to spread out and maybe spin-off the excess gas, making a line of fire below, which is very beautiful.”

Respect for the fire knife dancers

Now having the chance to see Samoan fire knife dancers every day, Sister Long said, “I am so impressed with the Samoan fire knife dancers and their performances. I’d like them teach me some of their tricks. I am just fascinated with how well they do. It’s awesome. I’m excited to see them toss their fire knives up to someone high on the mountain in the theater.”

“They are so professional, and I have never seen anyone twirl a fire baton as well as they do their knives — or even a regular baton. For every trick they do, I want to stand up and cheer. I know how hard they’re working and how accomplished they are. I never get tired of watching them.”

“We demonstrate how we do the fire knife dance every day in the Samoan Village,” Kap said, “and we also have an activity for guests who want to try twirling one, but of course without hooks and fire. Stop by.”

Try spinning a practice knife in the Samoan Village.

Mike Foley, who has worked off-and-on at the Polynesian Cultural Center since 1968, has been a full-time freelance writer and digital media specialist since 2002, and had a long career in marketing communications and PR before that. He learned to speak fluent Samoan as a Mormon missionary before moving to Laie in 1967 – still does, and he has traveled extensively over the years throughout Polynesia and other Pacific islands. Foley is mostly retired now, but continues to contribute to various PCC and other media.

Thanks for the interesting article about the fire knife dancers at the Polynesian Culture Center. Our family has visited the center in Hawaii several times and enjoyed the intertainment.

Having a sister missionary serving there currently is such a blessing.

Sister Long is an amazing missionary. We enjoyed the article featuring her BYU baton twirling experiencing.