In Part 2 of our series of La’ie during World War II, we learn from the recollections of Laverne Pukahi Joe Ah Quin and Gladys Pualoa Ahuna how martial law, declared immediately following the Japanese attack that brought the US into World War II, affected the local families of Laie.

BACKGROUND: Life In Laie After Pearl Harbor

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the army anticipated that the Japanese were going to land there in force. American troops took up positions around the perimeter of all the main islands, . They put up barriers on the beaches to deter landings and all of the airports in Hawaii were taken over by the Army with all private planes grounded. The ROTC units from the University as well as Hawaii Territorial Guard units were mobilized.

Immediate Repercussions: The Military Takes Charge

Soldiers by the Laie Curio store – Photo courtesy of BYU-H Archives and Special Collections

| “They couldn’t call anyone, they couldn’t write anyone. Everything was censored,”

Gladys Pualoa Ahuna |

By the evening of December 7, 1941, Governor Joseph Poindexter ceded all governmental control to Commanding General Walter Short, which placed all residents under military control. With that authority, the military instituted curfews, blackouts, control of the press and the temporary closure of public schools. It also allowed them to institute the draft and to call all men to come in and register for service and identification.

Gladys shared a personal experience from her family that illustrates the times dramatically: “My brother was a senior in Kamehameha School. Because he was in the ROTC, they took him right out of school and put him into the Hawaii National Guard, and from there, right into the Army.” Gladys’ hanai brother, which is a Hawaiian word for a child who is accepted into a family as a member, was also taken.

For three months, they heard nothing, which took a big toll on Gladys’ mother. Where were they? Were they being fed? Were they in any danger? Those worries plagued her constantly.

“One day”, Gladys shared, “my father had to go to the Haleiwa side of the island to work. Because he had a company truck, he was allowed onto military posts. There, on the beach, was my brother.” In fact, both boys were assigned to the same unit. It was a joyous reunion between father and sons. Now he could go home and set his wife’s mind at ease. But still, there was little communication afterwards.

Laverne Pukahi’s mom also worried for her children. “I had two brothers join the Navy, and one join the Army. I remember…. when my dad used to catch fish, my mom used to sit down outside and I’m sure she was praying. She used to write letters. She would make us pull some of her white hair out and put them in the envelope.”

Repurposing Laie

| They built a tower, maybe about 20 feet high, so that they could see the ocean.

Joe Ah Quin |

Most of the residents of Laie were faithful members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Laie was utilized as a farming community, with rich fields of sugar cane, taro and coconuts. Demographically, the population consisted of native Hawaiians and other Polynesians from various Pacific Islands, as well as a few residents from Canada and the U.S. mainland. There was also a strong presence of plantation workers from Japanese, Chinese and Filipino descent. Porteguese and Puerto Rican populations were also represented.

Courtesy of BYU-H Archives and Special Collections

The prominent building of the area was the majestic La’ie Temple, a place followers of the faith used for instruction, service and in sharing the saving grace of Christ with all mankind. The grounds also held a Visitors Center and expansive manicured gardens, popular with both tourists and local servicemen. The temple is still utilized today and is one of the most visited church sites on the island.

Entrance to Pioneer Cemetery

Above the temple stands the Laie Pioneer Cemetery, where many of the honored founding pioneers of Laie are buried. On the top of the hill, in the middle of the cemetery, is an open gazebo. From there you can see down to the beaches along the shore and out into the wide expanses of the Pacific Ocean. After the Japanese attack, the Army set up an observation post and remained there for the rest of the war. Certain areas of the cemetery became off-limits.

A section of the ‘new’ cemetery, situated about two blocks north of the temple was designated for military barracks. As mentioned in Part I of this series, the Telephone Exchange, close to Hukilau Beach, which was where Superintendent Peter Enos, his wife Sophia and their family lived, became the Command Post. As Gladys, described, “we became OP7. They built a shack at the back of the exchange for the soldiers who had to be on duty. They put a machine gun on our cesspool, and the laundry room was stacked with ammunition cans from the floor to the ceiling.”

The family had to gain permission from the guard to simply enter their yard. But Gladys also shared that the soldiers were good and respectful to her parents and all of their children. They became very fond of them all.

Living In an Altered State

Moses Hiram with his fishing boat in front of the barbed wire barricades – Photo courtesy of Laverne Pukahi

| “When they came back, the military was standing on the shore with their guns pointing at them. They didn’t know what was going on”.

Laverne Pukahi |

The restrictions affected life throughout the island. There were great rolls of barbed wire stretching across the shoreline and into the surf restricting both fishing and swimming.

“The families had to take care of themselves,” shared Joe, slipping into the local Hawaiian pidgen of his youth. “I mean, no more hukilaus (large group net fishing on the shores). No can go down to da beach and catch fish anymore, because all da barbed wire. It was restricted. My mother and father had to go down and buy cases of food. That is how we survived.”

One night, Laverne’s father, Moses Hiram, decided to head out with one of his sons to fish at Goat Island, as they always did. But the military, who were stationed to the north, saw their lights. Soon there were flashlights turning on and off rapidly. The guards were using Morse Code to notify security. When Peter and his boy came back, the military, and their rifles, were waiting for them. After determining that the Hirams were not a threat, the military explained that all of the little islands dotting the bay were now designated for military target practice. They remained off limits for the remainder of the war.

Immediately following the attacks, school was dismissed for almost 3 months. The buildings were utilized during that time to register every man, woman and child with the Federal Government, and each of them received a number. Gladys can remember that hers was #36-36.

Children from Hawaii became adjusted to wearing gas masks. Photo courtesy of the Honolulu Advertiser

March, when it was time to go back to school, each child was issued a gas mask. It was required that they carry the masks with them throughout the day, slung over their shoulder, along with a heavy canister.

“If we were in class when they rang the bell for a gas mask practice,” Gladys continued, “we had to pull the gas mask out and put it over our faces. The teachers would come along and place their hands over the canister. You would then have to breathe in.” If the mask was not airtight, it wouldn’t stick to the face and it would have to be tightened.

They also dug trenches at the school, and when they rang the buzzer signaling an air raid attack, the students would have to run out and jump in these trenches. Now, the schools had a strict dress code. All of the girls had to wear dresses or skirts. So the boys would run as fast as they could and jump in the trenches first and watch the girls climb over. Gladys took a group of girls and went to the principal’s office. You’ve got to change the dress code,” they explained, “and allow us girls to wear pants. And that” Gladys said proudly, “is how we were first allowed to wear pants to school”

When school returned to session, they children attended a shortened week. The available farm workers were in short supply. The children were sent to work the fields.

It was dirty work, especially in the taro patches. Gladys and Joe remembered that they would wash off the sticky mud at the pump and either head for the local swimming hole or down to a small section of beach that wasn’t barbed wired off to get the rest of the mud off….and for recreation, of course.

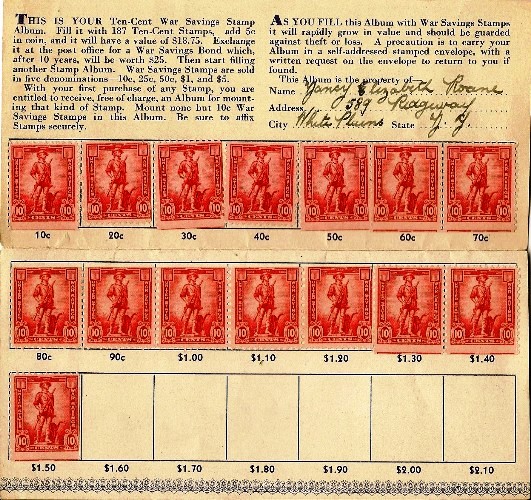

The front page of a war bond stamp book, Image courtesy of The National World War II Museum

The local children were also industrious in finding other ways to earn money. Laverne shared that whenever troops were traveling down the road by their house, they would follow after them dragging bags of coconuts that her brother had husked and prepared. “Coconut, Joe! Coconut, Joe!” they would call. He would sell them for 10 – 15 cents each. Her brother Tarzan would also sell coconut hats. When they were asked, “what are you going to do with the money”, they would proudly reply “we gonna buy war bonds!” They would then take the money and buy special stamps that they would paste into a booklet. When the book was full, they could buy a bond. The bonds cost $18.75, but when they matured, they were worth $25.

NEXT SEGMENT: Mixing It Up in Laie

PREVIOUS SEGMENT: Laie: Finding Refuge From the Storm

Nina Jones, a mainland gal from way back, is now a transplanted Islander. With her husband of 39 years, she volunteers at the Polynesian Cultural Center. Her hobbies include swimming, traveling, studying and writing about what she is learning from the various Polynesian cultures. Her blogs focus on their history, beliefs, practices and – as an added bonus – delicious food! To her, Polynesia is not just a place to visit, it is a way to live and she is very honored to be able to be a part of their amazing world.

Recent Comments