With all the attention recently focused on Cook Islanders currently appearing for six weeks at the Polynesian Cultural Center, it seems fitting that we introduce you to Patoa Benioni.

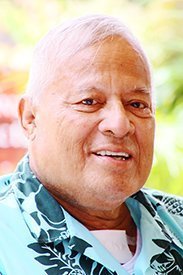

Patoa Benioni

The first Cook Islander at the PCC

More than 50 years ago, Patoa — who was born in Aitutaki in 1941 but spent most of his boyhood on Rarotonga in the Cook Islands — played a key role as an original Polynesian Cultural Center performer.

Today, almost everybody calls him Patoa or Uncle Patoa, but like some Polynesians, his actual name is much longer: Te Are Toa O Te Patoa o Maouna Tama Pikikaa Benioni. From an early age he was interested in education. For example, his grandmother selected him “to carry the knowledge and traditions of vairakau maori [traditional Cook Island “green medicine”] with direct lineage of 22 generations of healers.”

‘School in Samoa’

“The labor missionaries who came to Raro to build our chapels, said, hey, why don’t you go to school in Samoa,” Patoa recalled during the Polynesian Cultural Center/Laie Community Association kūpuna [elders] luncheon on July 19, 2017, where he was the guest of honor.

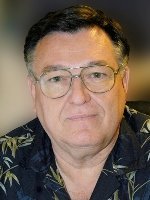

Mariaha Peters

Without a passport, he left Raro in the British-system equivalent of the eighth grade, sailed to Aitutaki in the northern Cooks, and caught a seaplane to Western Samoa [now independent Samoa]. Arriving but not speaking Samoan, a friendly official told him, “Go catch the bus,” which dropped him off at Pesega, the Latter-day Saint Church compound near the capital of Apia. He remembers thinking the Church College of Western Samoa (CCWS) “was huge, over 3,000 students.” (Under the British system in those days, a “college” was more like a U.S. high school.)

Patoa’s wife, Juanita Chang Benioni, picked up the story at the luncheon:

“Fortunately, he knew one person there, and that was [mission] President Howard Stone [who lived in Laie for many years]. Patoa stayed in the mission home a little bit; and the story goes that every Sunday the stake president would get up and say, we have a young man here who wants to go to school, but he has no place to live.”

Juanita pointed out the oldest kupuna at the luncheon, 94-year-old Mariaha Peters, “the woman who is so important to my husband: It was Mariaha and Patrick Peters who went and found this young man sitting under the breadfruit tree at the mission home. They didn’t know him, but they took him home, and from that moment on he became their son. To this day when he talks about his mom, it’s this mom [Mariaha].”

‘I had never heard of algebra’

Patoa recalls while sitting under that tree “that’s still there today, these two teachers came to me and said, ‘Are you going to school here?’ They asked me what grade I was in. I told them form 4 [equivalent in a British-based system to about the 10th grade]. I never went to form 1, 2 or 3; I went straight to form 4.”

“The teachers took me to their algebra 2 class. I had never heard of algebra. I almost ‘died,’ but I hung in there, and passed.” Patoa said he also passed typing and homemaking — cooking — that first year.

“So many people pushed him to go to school,” said Juanita, resuming the narrative. “There was no electricity in the home, so he studied every night by the light of a kerosene lamp. He never forgot those days and the many sacrifices that were made for him to go to school

‘No Polynesian Cultural Center yet’

She said after he graduated from CCWS, Patoa worked for a while in New Zealand and then in 1961 the Peters sent him to what was then called the Church College of Hawaii (renamed BYU–Hawaii in 1974) in Laie for a university education. “When he came here, there was no Polynesian Cultural Center yet. It was under construction. Parts of CCH were still under construction, so he worked in the pineapple fields with a bunch of boys from Samoa over the summer.”

“During registration for school,” Juanita continued, “they were all lined up. Professors Wylie Swapp and Jerry Loveland walked down the line…and hand-picked young Polynesian men and women to become part of what was called the Polynesian Institute.”

“My husband was really shy at that time, but Dr. Swapp said, ‘You are the only Cook Islander we have. ‘What can you do? I can drum a little bit. I can sing a little bit, and I can dance.’” Patoa became one of the first dance instructors in the Polynesian Institute.”

The Polynesian Institute

“The Polynesian Institute then put on a program called Polynesian Panorama, and that went to the Waikiki Shell and the Kaiser Hawaiian Dome. Polynesian Panorama was the trial to see if authentic Polynesian dance and music would sell; and it was sold-out every night. At that time labor missionaries were still building [what would eventually be called] the Polynesian Cultural Center.”

Therese Cummings

“I started the Cook Islands group,” Patoa picked up the story. “I taught the Samoan and Hawaiian boys drumming. We gave performances in Waikiki, and when we were finished, we would go help at Hukilau Beach for the ward [fundraising luau].”

Tahitian schoolmate and “sister” Therese Cummings, 78, recalled, “I couldn’t speak English yet, but I was happy to meet Patoa. Even though he’s Rarotongan, we could communicate with each other. As the years went by, PCC was organized. We were the first people to come here and work in the villages. Patoa was also working in the Tahitian Village. He was one of the blessings I had. He was my ‘brother.’ We took care of each other.”

As the PCC was nearing completion in October 1963, Patoa recalled his first job was to cut coconut fronds so volunteer Samoan women from the community could weave them into large pola blinds to cover the fence. “We also planted some of these coconut trees [gesturing]: When we started, they were short. We brought them from all around the island. Some of these trees are more than 50 years old.”

More dancers on stage than visitors in the audience

“When the Center first opened, Patoa used to say, there were more dancers on stage than there were visitors in the audience.” He also told of how the villagers in the first year would dress in their costumes and stand by the side of Kamehameha Highway, trying to encourage tourists to turn in.

Patoa Benioni (left), drumming for original Polynesian Cultural Center Tahitian employee friends (left-right) Etua Tahauri, Tekehu Munanui and Therese Cummings.

Long-time friend Pulefano Galea’i, “father” of the Center’s Samoan World Fireknife Championship who’s now a retired senior PCC manager, remembered Patoa from those days as “a great singer, leader, composer, and a great drummer. But one thing he always had in mind, he wanted to bring people here from the Cook Islands. He made a great proposal to the Polynesian Cultural Center and BYUH to have a Cook Islands village inside; but instead, they all worked in the Tahitian Village.”

“Yesterday [7/18/17], Patoa and I sat together watching a full-fledged Cook Island group. They’re here right now. Don’t miss it: It’s the greatest performance I’ve ever seen.”

“Patoa, you can never be forgotten for all that you’ve contributed to the Polynesian Cultural Center, to Laie, and to all of us,” Galea’i said.

Juanita Chang Benioni (right), with the earliest guides at the Polynesian Cultural Center.

Committed to education for his people

Juanita told the kupuna luncheon crowd, “Patoa made me promise when we met that after we graduated, we were going back to the islands and give back to the many people who sacrificed that we could go to school at Church College of Hawaii and that we could work at PCC to help pay for it.”

She pointed out Patoa graduated from CCH in 1969 in vocational education, and then worked for a year as a carpenter in Waikiki while she finished her degree in 1970 in teaching English as a second language. Soon after the American Samoa government hired the couple.

They lived there for 10 years. Patoa was the Director of Vocational Education and Juanita taught high school English. During that time, they both also earned master’s degrees through BYU (Provo), and he developed the territory’s first vocational center in Tafuna, which is now a prominent technical high school.

Returning to Laie in 1980, Patoa worked for BYUH Physical Facilities and served on the Laie Community Association board. He transferred to BYU (Provo) in 1993, and retired from there. The couple moved back to Hawaii in 2012, and now live in Waianae.

Still committed to education, the Council of Elders of the Dr. Agnes Kalanihookaha Cope Traditional Native Hawaiian Healing Center in Waianae named Patoa a member in 2013, and certified him in lā’au lapa’au and ho’oponopono [traditional Hawaiian medicine and conflict resolution, respectively] in 2016.

“I would like to thank my mother, Mariaha Peters, and acknowledge her for her support for encouraging me to continue to go to school,” Patoa said at the luncheon. “I would also like to thank everyone here. It’s a great honor.”

Story and contemporary images by Mike Foley, who has worked off-and-on at the Polynesian Cultural Center since 1968. He has been a full-time freelance writer and digital media specialist since 2002, and had a long career in marketing communications and PR before that. He learned to speak fluent Samoan as a Mormon missionary before moving to Laie in 1967 — and still does. He has traveled extensively over the years throughout Polynesia and other Pacific islands. Foley is mostly retired now, but continues to contribute to various PCC and other media.

Good afternoon from Pine Hill, New Mexico. I am full Native American, in 1962 i was a young Marine stationed at Kaneohe Marine Air Staion. I married a beautiful Hawaiian Lady named Nani Kamae, Nani and her parents were the first Hawaiian entertainers at PCC. I attended CCH and worked part time during the school year at PCC as a guide. During the summers i worked in construction. I enjoyed Patoa’s happy ways and his talents, especially the drumming.

I lost my wife to cancer in 2009 and continue to work in education helping my people, i just talked to a 4th grade class about being organized. Alot of the young people are neglected and need guidance for the older generation. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to write my message. Craig Brandow

What a lovely message, Craig. We join you in sweet memories of Nani and her family. Much respect for your work with your keikis. We will send your best to Patoa and hope that you get to visit us again soon at the PCC.

Thanks for the memories.I came to Laie CCH in 1962.My good friend Dennis Singh and myself assisted in building the Fijian village under the direction of Ratu Isireli Racule who composed the Fijian song Bula laie.During those early days at CCH we particularly knew each other.Patoa was a fun loving person.When he got married to Juanita we used to have dinner at my place.Kudah Hafiz.Daud Sahim

Thank you for sharing this memory. We are so grateful for wonderful examples such as you and your friends and work mates. BTW, the Fijian Village is now going through a bit of a ‘sprucing up’. We are excited to be preserving and supporting the wonderful work of our founding elders. We love the Fijian Village and will be showcasing the progress in a couple of months, so stay tuned!

In 1965 I entered CCH as a freshman, Dr. Cook was our college President, my brother Dennis was serving a mission in the Philippines, David/Daud had graduated and working in Honolulu, Patoa and Junita were living in Laie and attending CCH. I have never forgotten my undergraduate days at CCH and working several jobs at PCC, CCH and in the summer driving a cab in Waikiki. I wish there was a way to connect with my brothers and sisters from the past.

Thank you for sharing your memories with us. You might consider joining the “i love byu hawaii & pcc” Facebook page. I seem many people reconnect there. If your friends are not on the page, someone who knows them probably is!