Ha: Breath of Life completes the Polynesian Cultural Center experience every evening in the Pacific Theater. People love this circle-of-life production that follows a young couple fleeing from a natural disaster, the birth of their son Mana, his coming of age and more — all performed beautifully through the perspectives of the various islands we represent at the PCC.

Most of the cultural insights are obvious and pleasingly portrayed, but there’s at least one cultural “nugget” in the Samoan section of the Ha — when the young man Mana is smitten by the beautiful Lani — that you might have missed:

The “sacred relationship” between a Samoan brother and sister

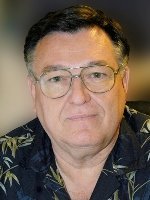

Lani’s brother (right, here portrayed by Boyd Lauano), scolds Mana (portrayed by Sonetana Falevai) for getting too friendly with his sister

When it becomes apparent that Mana and Lani like each other, her brother quickly steps forward and chases him away — several times, before he requires Mana to prove his abilities and intentions, not only to him but the entire village.

Now some in the audience might mistakenly think the brother-character is a jealous suitor with prior claim, but no, Lani’s brother is fulfilling his Samoan family and cultural obligations to his sister. In fact, this relationship was so important in old Samoan culture that it’s summarized in a proverb still used today:

O le i’oimata o le tuagane o lona tuafafine.

(The pupil of a brother’s eye is his sister)

Boyd Lauano, who formerly acted the role of Lani’s brother in Ha: Breath of Life, as well as performing the role of Mana, is still performing as a fire knife dancer on the island of Oahu. “A brother is always supposed to protect his sister,” Boyd shared. “Our old saying compares this responsibility to how careful he is with the pupil in his own eye.”

The late Aumua Mata’itusi Simanu, a widely respected female talking chief and professor of Samoan language and culture at the University of Hawaii/Manoa, described the brother’s responsibility as a va pa’ia — a “sacred relationship.” For example, she said it wasn’t appropriate for an unknown young man to talk to a young woman . . . without first talking to her brother and family.

Lauano agreed and worked with Maliana Ava, the current Samoan section leader for Ha, and others to include this element in the storyline. “When the brother sees that Mana has already approached his sister, he doesn’t like it, and the whole village comes out to support him. The brother stands between Mana and Lani, because Mana is an outsider and they don’t know anything about him.”

Does the custom still hold true in modern Samoa?

The brother makes Mana walk through fire to prove his intentions with Lani

In Ha Mana quickly proves his worth, especially after literally walking through fire for his sweetheart . . . it is his commitment and willingness to prove himself that helps the brother and the rest of the village come around.

Mana (portrayed here by Ricky Suaava) makes peace with Lani’s brother

But does this custom still hold true in modern Samoa? Lauano, who first came to Laie in 1998 to study at BYU–Hawaii and dance at the Polynesian Cultural Center, says it does in many families, including his own.

“We always learned, from way back in Samoan culture that no matter what, as brothers you take care of your sister. You have to be there for her,” Lauano said. “I grew up in Lotopa, near the capital of Samoa. I have one sister and three brothers, who are now spread all over from New Zealand to the U.S. mainland. And even though she’s the eldest and still lives in Samoa, our sister-to-brother relationship is still important to us.”

“I grew up this way. I also saw how my six uncles took care of my mom and her sister in their generation.”

“Today, my brothers and I still contact our sister two or three times a week.”

Becoming more aware of your own culture

“We have another saying back in the islands that it’s hard for a sister to have a boyfriend because of her brothers,” Lauano continued. “That’s the custom we portray in Ha, although now days many people back in the islands and other parts of the world are more western in this respect. That’s why Lani’s brother is hard on Mana. Traditionally, he should have come to the family first. That’s the Samoan way.”

Lauano added that when he first came to Laie, the Polynesian Cultural Center helped him to become more aware and proud of his own culture; and he always remembers a lesson one of his early instructors instilled in him: “When you perform on stage, you dance with your heart.”

“When I became a supervising lead, I taught the same principle. Anyone can entertain, but it’s another thing to represent your culture with pride. For what I learned and have shared, the Center will always be a part of me.”

Story and photos by Mike Foley, who has been a full-time freelance writer and digital media specialist since 2002. Prior to then, he had a long career in marketing communications, PR, journalism and university education. The Polynesian Cultural Center has used his photos for promotional purposes since the early 1970s. Foley learned to speak fluent Samoan as a Latter-day Saint missionary before moving to Laie in 1967, and he still does. He has traveled extensively over the years throughout Polynesia, other Pacific islands and Asia. Though nearly retired now, Foley continues to contribute to PCC and other media.

Story and photos by Mike Foley, who has been a full-time freelance writer and digital media specialist since 2002. Prior to then, he had a long career in marketing communications, PR, journalism and university education. The Polynesian Cultural Center has used his photos for promotional purposes since the early 1970s. Foley learned to speak fluent Samoan as a Latter-day Saint missionary before moving to Laie in 1967, and he still does. He has traveled extensively over the years throughout Polynesia, other Pacific islands and Asia. Though nearly retired now, Foley continues to contribute to PCC and other media.

I had the immense pleasure of seeing Ha, Breathe of Life in September 2017…it was one of the most moving experiences of my life.

Thank you for coming to visit us and for your appreciation of our evening show, “Ha: Breath of Life”. So much work, as well as love has gone into this production. We all love it too!

It was amazing. I learned so much there and can’t wait to go back!