PCC Restores Waka Taua

As indicated in The King’s Canoe, the PCC’s Maori waka taua is currently being renovated — this time by PCC master carver Kawika Eskaran, a Hawaiian who also played a key role in carving BYU–Hawaii’s 57-foot traditional twin-hulled Hawaiian sailing canoe Iosepa, that’s now berthed in our Hawaiian Village when it’s not out on the ocean.

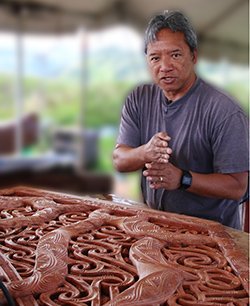

Kawika Eskaran, Master Carver at the Polynesian Cultural Center

Eskaran — who initially apprenticed under the late Wright Bowman at Kamehameha Schools — recalled working on the waka for the first time over 30 years ago as an apprentice to the late Epanaia Barney Christy. Uncle Barney, as he was affectionately called, was a Maori master carver who himself had been one of the apprentices under master Maori carver John (Hone) Taiapa in the early 1960s when they were initially putting together the carved houses for the PCC’s then-brand-new Maori Village.

“The last time we did a restoration on the canoe was in 1980, when most of the eight carvers here at the Cultural Center were apprentices — Ken Coffey, myself, Jared Pere, Doug and Angus Christy and others — under Uncle Barney,” Eskaran said. “It took us almost three years at that time to restore the canoe.”

“The restoration that we’re doing today is even more extensive than that, but we’re trying to do it in a cumulative total of four working-months.”

He explained he and a few others are about half-way done with their work on the 60-foot-long 40-man waka taua: “At first we were going to take care of the major issues. We were just going to take it apart, clean the pieces, and re-rope it. For example, in the center-bottom of the hull there is a drain hole, and the termites got into that section. I had to cut out that piece, and then inlay new pieces so it couldn’t be detected.”

“The cracks in the canoe required weeks of work,” Eskaran continued. “Doug Christy and I cut out all the cracks and inlaid fresh pieces of wood. We glued them in, and after finishing them down to bare wood, they match perfectly with the existing curvature and other aspects of the canoe. You can’t even tell that the canoe has been patched.”

“I also wanted to keep the scalloped undersides that’s a prevalent feature on the bow’s keel. If you look closely, there are rows of curved lines that have been carved into the canoe. Uncle Barney told me the curvature of those lines create bubbles that help elevate the keel in the water. So, we didn’t want to carve away those purposeful cuts.”

Eskaran said another challenge this time “was to change the interior of the hull from it’s original V-shape to half-round curvature.” He explained the V-shape was a result of using hand-axes, carving, from one side to a definite line in the the center-bottom, then chopping from the other side to the center. “We wanted it to have a more traditional, rounded look. That took weeks to do.”

Currently the hull has been patched, primed and returned to the Maori Village, where it bears a marked resemblance to its original form back in the forest near Kaikohe, North Island, New Zealand. “Everything else has been taken off: All of the strakes or sideboards, the ‘ear’ pieces that the seats sit on, the steering oars, the taurapa and tauihu or ornate tail and nose carvings, respectively.”

Eskaran explains the details of the canoe’s “nose” carving.

Pointing to the tauihu, Eskaran said, “There have been at least a hundred repairs on this piece. One of the problems we’re seeing, because of the variety of cracks running right through the entire piece, is that it was ready to collapse.” He explained he cut the biggest crack out, then inlaid replacement pieces from both sides, “and matched everything up: Even the bodies of the beings, the curvature and contours all had to match up with the existing carving. Every single thing in here has been replaced with the same kind of wood. The wood itself is beautiful, but these will be painted a traditional red Maori color.”

“I wanted to get back to the original carving. When Jared Pere and I are finished, it will be pristine and beautiful.”

“The war canoe captures so many things on so many symbolic levels. It’s not just its beauty, but there’s a message being shown through the carvings. All of the surface designs have meanings; nothing is put on here just as mere decoration. This tauihu, for example, tells of [the demi-god] Maui and the separation of the heavens and the earth by the children who pushed the parents apart. Once that happened, light and knowledge came into being on the earth.”

Eskaran added that the taurapa [stern piece] is also a representation of the “light and knowledge” that came to earth. He recalled Uncle Barney told him one of the reasons the taurapa is taller than the tauihu is to help the upright balance the canoe, similar to how a tightrope walker sometimes carries a pole. “This is kind of like that ‘bar’ for the canoe.”

“This is a work of love, and it’s great to work at the Center where I can use my gifts and passion,” Eskaran said.

Story by Mike Foley

Mike Foley, who has worked off-and-on

at the Polynesian Cultural Center since

1968, has been a full-time freelance

writer and digital media specialist since

2002, and had a long career in marketing

communications and PR before that. He

learned to speak fluent Samoan as a

Mormon missionary before moving to Laie

in 1967 — still does, and he has traveled

extensively over the years throughout

Polynesia and other Pacific islands. Foley

is mostly retired now, but continues to

contribute to various PCC and other media.

Recent Comments