Tongan feasting: A Serious Custom

[Author’s note: I have attended Polynesian feasts where they cooked 200 pigs, and fed thousands of people . . . but the first time I sat down at a Tongan kaipola feast, I was truly impressed.]

An expression of love and gratitude

“I feel that Tongan feasting is driven by the same principles on which the American Thanksgiving holiday is based. It truly is an expression of love and gratitude. Also, it involves a sense of duty to maintain relationships among family and community members,” said Alamoti “Moti” Taumoepeau, manager of the Polynesian Cultural Center’s Tongan Village.

You could say Taumoepeau came by his position through a legacy: He was born at nearby Kahuku while his parents attended BYU–Hawaii and worked at the PCC, and his grandfather served as “chief” of the PCC’s Tongan Village.

When his parents finished their studies, they returned to Kolofo’ou, near Tonga’s capital of Nuku’alofa when Moti was four years old; but he returned to Lāʻie as a young man and has been here since. “Half of my life has been here in Hawaiʻi,” he said.

“Whenever there’s a feast involved, whatever the occasion may be — especially at the village-level, the people will always hold a fono, a meeting to divide responsibilities: Who’s going to bring what to help accomplish the purpose for the occasion. That’s why a Tongan feast is so encompassing. You will never find just one family or individual doing the work alone. When they lay out the kaipola, the food table, it’s the efforts of many people working together,” Taumoepeau continued.

‘Heaped with food’

He explained that in modern times a kaipola is a Tongan feast somewhat like a Hawaiian lūʻau: “The first part of the word, kai, means ‘eat’ and a pola is a large mat up to 10 feet long that’s made by splitting a coconut frond down the middle stem and weaving the two halves together to form a ‘table’ or serving tray. This would be heaped with food. Historically, guests would sit on the ground on either side of the pola and eat with their fingers. Today, of course, we lay out the feast on regular tables.”

“There will be whole-roasted suckling pigs and the best kind of meat that we can find, including beef and fresh catches from the ocean. A real delicacy, of course, is lobster.”

“Then there’s the lūpulu, which is very popular,” Taumoepeau said. He explained that’s a delicious combination of coconut cream; corned beef (the pulu part of the name, from the English word “bull”), seasoned to taste with onions, salt, maybe some tomatoes and/or other condiments; and soft, young taro leaves (the lū part of the name), which are layed out now days in a aluminum foil pan somewhat like a lasagna and baked together. When the meat part is changed, Taumoepeau added, the dish is then called lūsipi (baked lamb _ i.e. sheep or sipi), lūika (baked fish) and so forth.

Large ceremonial pigs are different

Large ceremonial pigs are different

Taumoepeau pointed out there’s a difference between the spit-roasted piglets served at a feast and the large partially-cooked pigs that are presented during Tongan and other Polynesian ceremonies.

“Those pigs are definitely part of a ceremony during which certain things are presented,” he said. “In addition to the pig, these include kava [which is used to make a traditional drink said to relax people] and yams; and we’re not talking about small things:

It has to be a large, mature pig, maybe weighing 300-400 pounds, and especially ones where the tusks are showing. In the highest form of presentation, say to the king or a noble, such pigs are dragged out on a vaka or boat-like sled, with the pig laid on its back. Sometimes many men and women will pull the vaka with a long rope. The underlying symbolism there is humility and submission.”

It has to be a large, mature pig, maybe weighing 300-400 pounds, and especially ones where the tusks are showing. In the highest form of presentation, say to the king or a noble, such pigs are dragged out on a vaka or boat-like sled, with the pig laid on its back. Sometimes many men and women will pull the vaka with a long rope. The underlying symbolism there is humility and submission.”

He added after the ceremony such pigs are “chopped up and usually divided among various families to use later.”

Then there are the starches: “We also always have to have starch, but just as there’s a hierarchy in Tongan society, food is categorized as well. For example, the starch crops that the Tongans value the most are the ones that are the hardest to grow and maintain. The most important one is the ufi or yam; they would always be number-one for families to look for to put on the table. Probably next to that is taro, then kape — a large tuber plant, and kumala or Polynesian sweet potato. You would rarely see manioke [tapioca] at a kaipola. That’s the least valued starch.”

“A lot of work goes into preparing such a feast, which is also an expression of love. The more that you give, the greater the expression of love; that’s the reason the food is literally heaped on the table.”

“At a feast, the most important people would be seated at special VIP tables, while the other tables would be open to regular guests; and when they’re done, another set of guests might come and enjoy the feast as well. When everybody is done, the host family or village encourages the guest to take food home. They do not take anything back: That would be considered selfish; you do not take back something you gave.”

Asked what is the largest feast he has seen, Moti responded, “Uike heilala, a week-long festival celebrating king’s birthday in July. The red heilala is our national flower. [the endemic Garcinia sessilis]. “The whole of Tonga is involved. A district will be assigned one day to serve the king breakfast, lunch and dinner. Literally there are thousands of people every day with hundreds of pola laid out in the field for everyone to come together and eat. These pola are usually eight-to-ten-feet long; and each pola would have, say, 10 suckling pigs, lots of lūpulu, fish, yams and sweet potato.”

“As you might imagine, it’s all hands on deck for such an undertaking. Everybody works. It takes hundreds of people to make it happen.”

For smaller occasions

“Just like bigger events, different responsibilities are delegated within the family to perform for smaller events and parties. Mom and the girls, and all her sisters, pretty much have their duties already laid out,” Taumoepeau said. “Father and the boys, they have their duties. Everybody has to help work”.

For example, Taumoepeau described how he recently helped put on a wedding feast for his brother. “Because my mom is the oldest, a lot of her siblings look to her to give the assignments. Those that weren’t able to come to Hawaiʻi sent money; those that did come were given assignments: Those from Tonga had the responsibility to provide mats and tapa [bark cloth] that are given as gifts to the bride’s family; and because there are not a lot of our family members here in Hawaiʻi, we opted to cater the meal. So in this case, rather than hands-on work, everybody had to share in the expense of providing the catered feast.”

“Of course, those who live here provided lūpulu, ota ika [raw fish in coconut cream, vegetables and lime juice], and of course we had to have puaka tunu — the roasted suckling pigs. That’s my favorite. Everybody chipped in.”

The amount of food is amazing

“I remember when I was growing up in Tonga there were times when we had to feed our missionaries, or on Sundays we not only had to make food for ourselves but we also had to make sure we had sufficient for our neighbors as well. That’s also part of the spirit of Tongan feasting, as I was taught. It truly was a way that we expressed love and gratitude. This is the form that we knew. When a person was given food, he knew how much we loved and appreciated him.”

“Coming from a country that is considered poor, we literally did not have a lot of material things,” Taumoepeau said, “but the amount of food we put out was amazing. You have to wonder, where did it all come from? Fortunately, many of the Tongan islands are very fertile. One of the meanings of the word Tonga is ‘ garden.’ Happy Thanksgiving, everyone.”

Memories of Christmas in Tonga

Sia Tonga

Two of our Tongan PCC managers who grew up in the Friendly Islands share some of their fond memories of Christmas in the Friendly Islands.

Alamoti Taumoepeau, Tongan Islands manager, who grew up near Nuku‘alofa, the kingdom’s capital; and PCC emcee coordinator Telesia “Sia” Afeaki Tonga from Mu‘a, which is also on the main island of Tongatapu.

Feasting, of course, and church

“Christmas to me was when families would set aside time for much prayer and going to church,” Taumoepeau recalled. “I was surrounded by families who were of the Wesleyan church as well as Catholics. There were very few of us who were Latter-day Saints (Mormons). All my friends, that’s what they did, and my family went along with that: Christmas was a time for church-going.”

“Every evening everybody would go to church, and we would have our own family prayers. After that, the fun would always begin. There would be groups of men and women who would carol Tongan-style, with all these old instruments, kind of like a home band. They would go from house to house, and when they arrived, we would always have to give them gifts.”

“It was also a time of feasting. Tongans, you will find, love to eat, and any holiday, any reason they can hold a feast, they will eat. Christmas was one of those occasions.”

“Of course, my parents had spent time in Hawaiʻi, so we also had a little Christmas tree. I remember my first one was white plastic; and, of course, we had little gifts that they were able to afford early on Christmas morning. Later in the evening everybody was busy, coming around caroling and feasting.

A horse-back Santa

“I realize, looking back now, that I was privileged more than other children in my town. My father was a member of parliament, and my grandpa was also, so we always had a little bit more than everybody else around us,” Sia Tonga said.

“One of my best memories is of my father, Viliami Afeaki, getting in a Santa suit and riding a horse through Mu‘a, with everybody looking at him like it was so peculiar. He didn’t need a pillow in his shirt, because he was a man of regal stature; but the thing they loved the most, he filled bags full of every kind of candy he could think of from Tonga and New Zealand, and he would give that candy to the kids up and down the streets. I remember feeling so proud that my dad not only got to be Santa Claus, but to see how happy all the kids were to receive a little of the candy I often took for granted. It was there, at a very young age, that I realized Christmas is so much more about giving.”

“In Tonga, around Christmas time and especially leading up to the New Year, the number-one highlight were me’a lea — groups of make-shift bands who used whatever instruments they could, sometimes cans, who would go and sing Christmas carols at homes.”

“The other thing, it didn’t matter what denomination you were from, around the holiday season we always ended up at a pola [feast] during the uike loto or the week of prayers that the Methodist families always held.”

“Our family also had a Christmas tree. My father was from a family of 11 — he was number-seven. The tree was whatever they could get that kind of resembled a pine tree. Under it we didn’t have very many gifts; it often ended up being lollies — sweets from New Zealand, so at least every one of the grandchildren had something to open. It might have been a small toy. They weren’t very expensive, but we looked forward to the tree and the gifts. Not every Tongan did that, but I’m thankful we had that tradition.”

***Originally Published 11/24/2015. Updated 12/17/2025***

Story by Mike Foley

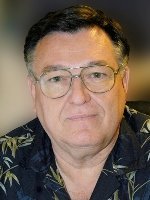

Mike Foley, who has worked off-and-on

at the Polynesian Cultural Center since

1968, has been a full-time freelance

writer and digital media specialist since

2002, and had a long career in marketing

communications and PR before that. He

learned to speak fluent Samoan as a

Mormon missionary before moving to Lāʻie

in 1967 — still does, and he has traveled

extensively over the years throughout

Polynesia and other Pacific islands. Foley

is mostly retired now, but continues to

contribute to various PCC and other media.

Recent Comments