Samoan dancers in the early days at the Center

Lā‛ie is a small town. It always has been. Statistics for the 1960s don’t exist, so it’s hard to chart its growth from that time. But even after more than 60 years of establishing the organization that provides jobs and education for its citizens, the town’s population is under 6,000. Add to that approximately 3.000 students at BYU-Hawaii for most of the year, and it still easily qualifies as little. And though Lā‛ie is a respectable size as towns on Oʻahu go, it has become something larger than itself: a destination for nearly a million tourists every year. How did that come about? And why does it continue to be true, year after year? To understand the evolution of this place, we need to trace its origins.

Pu’uhonua

From ancient times, the area around Lā‛ie had been considered a puʻuhonua, which is a place set apart as a refuge. Puʻuhonua were places where those who had made mistakes—even broken laws—could seek sanctuary, repent of their wrongdoings, and start again. Though the physical signs of the puʻuhonua are gone, the feeling of sacredness that had been there for hundreds of years lingered.

Skipping forward and leaving out many interesting details, Christian missionaries began arriving in the early 1800s. Calvinist Protestants came in 1820. The Catholic Church established their Sandwich Islands Mission in 1827. The Christians brought Western ideas, and some were adamant that all previous island habits be replaced with what they considered “more civilized” practices.

Missionaries from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints arrived in 1850. In early 1865, leaders of the Church, sensing the ancient spirit of the place and wanting to serve the growing number of converts to their faith in the area, a bought two ahupuaʻa (land divisions) comprised of 6,000 acres to make Lāʻie Hawai‛i’s church headquarters and a gathering place for church members. There was little in the way of jobs there, so people didn’t relocate in large numbers at first. Still, the townspeople built a chapel (1887) and a mission home, which provided work for some of them; and they began making plans for other infrastructure.

The original chapel, 1887.

They established farms and built a sugar mill. Those became the biggest endeavors and offered employment to people who continued to come to the area. Over time, Church leaders were able to see the value in reviving dance, music, and other aspects of the culture, and building upon those.

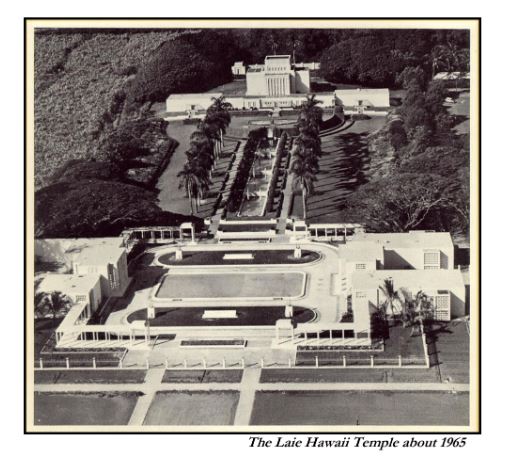

By 1915 the community was ready to receive the gift that most embodied its earlier status of puʻuhonua: a temple of the Lord. This would be just the fifth temple built by the Church, and the first one not on the mainland. It was a high honor. The temple was dedicated in 1919, and stands today as a living, vibrant call to those who seek the refuge of forgiveness and new life.

Aerial shot of La’ie Hawai’i Temple, 1965

Challenges Met

Life was not without challenges, however. One of the hardest came in 1940, when the chapel the members had so painstaking built in 1887, burned to the ground. It was devastating to these people whose lives revolved around their church community. They had no money, and as World War II engulfed the Pacific, no materials to buy. They held meetings in a social hall for the next several years.

After the war, they began exploring options that would help them rebuild.

One of their common practices for food gathering was to go as a group to the beach and cast out a fishing net. Then everyone in attendance would work together to pull in the catch (hukilau). The catch was divided between the participants.

The North Shore of O‛ahu was not a destination at the time, except for the tour buses that brought people to take pictures of the stunning white temple. Sightseers did come by sometimes—often they were servicemen looking for interesting things to do. Some of them offered to pay for the privilege of helping pull in the nets. Word spread, and more servicemen came. Then an idea was born: they could raise money by holding hukilau, followed by lūʻau. They would charge admission to the dinner on the beach and entertain the guests with Hawaiian music and dancing.

It didn’t take long for people to hear about the festivities. In an era when there was much less to do on the island, this was a new and fun idea. The people of Lā‛ie began advertising the events, which were sometimes held twice a month, and people came—in droves. The first “official” hukilau in January 1948 was attended by over 1,000 people.

Hukilau! 1940s

The local men laid out the nets and helped the tourists pull them in. They also prepared the imu, the underground ovens in which the catch would be cooked. The women prepared the other foods, and they and the children served guests. People of all ages danced. It was a major event for everyone.

In 1950, the Church dedicated a new chapel. By then the hukilau was a well-established attraction. Audiences continued to grow. The organizers realized they needed to develop facilities that would more comfortably accommodate their guests; thus, the idea of the Polynesian Cultural Center came into being. Plans for its construction coincided with those for another pillar of the community development plan.

The Next Phase

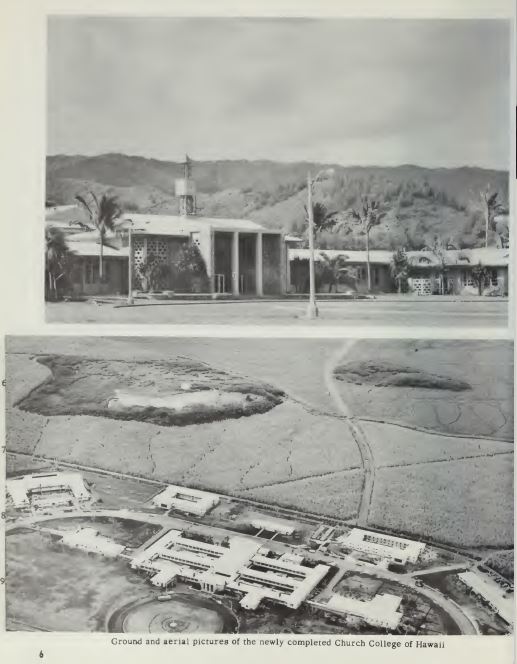

Remember that the Church had dedicated their temple in 1919. Afterward, workers were tasked with improving other aspects of Lāʻie’s infrastructure. Part of the design was to build a university near the temple. Though leaders had begun to explore that idea in 1921, the groundbreaking for the Church College of Hawaiʻi didn’t take place until 1955. It’s first ten students graduated with associate’s degrees in 1958, and building continued well into the 1960s. Construction of the Polynesian Cultural Center began in 1962.

New Church College of Hawaii, 1963The purpose of the Church College of Hawaii (now Brigham Young University- Hawaiʻi) was to help people, particularly natives of Pacific Rim nations, get higher education in a way that had not been available to them before. The Polynesian Cultural Center provided program by which the students could earn part of their tuition and living costs by working a few hours each week when they were not in classes. (By current law, they are limited to 19 hours per week.) The rest of their expenses would be covered by the funds brought in by the Center. As the Center is a nonprofit organization, all proceeds then and now have gone to support the students.

Working on the Polynesian Cultural Center’s lagoon

The Polynesian Cultural Center, shortly after completion, 1963

Lā‛ie Today

Though not without bumps along the way, the plan has worked exceedingly well. At any given time, about 70% of the workers that guests meet in the island villages and around the Center are students, loving the opportunity to share their cultures and the Polynesian spirit of aloha. Students have commented that as they are presenting their nations’ dances, music, and customs, they are only doing what they would normally do for free, and sometimes learning about their own histories in greater depth. They are happy able to use those skills to enlighten and entertain visitors as they earn their way to more abundant lives.

The Polynesian Cultural Center’s Island of Tonga Village in the 1960s

The attractions that have developed on the North Shore have made this part of Oʻahu a major player in tourism in the Islands. According to a history published on the BYU-H website about 2015, “[when the college was announced in 1955,] the annual visitor count for the entire state of Hawaii was only 110,000, but since the opening of the Polynesian Cultural Center in 1963, over 37 million people have visited Lā‛ie [alone].”

Samoan dancers in the early days at the Center

For the students who have passed this way, the results are life altering. Currently, students from 62 countries represent the BYU-H student body. They often come to Lāʻie shy and inexperienced. They leave with a greater understanding of the world, greater empathy for people of other nations, greater skill to elevate their home economies, and greater capacity to lead the way for the rising generation.

The students enjoy presenting their island dances.Lāʻie is little in a very big way. The townspeople provide the core. Those who come with willing hearts and with service in mind help to expand the spirit of aloha, welcoming visitors from near and far. Lāʻie continues to be a haven. She is proud; she is strong; she is majestic; and she offers aloha to everyone.

Aerial view of Polynesian Cultural Center today

Thanks to Mike Foley, a long-time resident and official Lāʻie and Polynesian Cultural Center historian, and to Maurice Moʻo, BYU-H Strategic Enrollment Senior Manager.

Recent Comments