As the saying goes, “It takes a village to raise a child,” and this couldn’t be truer for the making of the Huki costumes. At the heart of this creative journey is Jesse Allred, the seamstress supervisor at the Polynesian Cultural Center. Despite having no formal training and being mostly self-taught, Allred has become an integral part of the team. Driven by a passion for understanding how things are put together, she began her journey as a seamstress between the ages of 12 and 14 and has been developing her skills ever since. Now, after a year and a half at the Center, Allred has brought her expertise to the Huki production, playing a key role in the costume design process.

Bright green lavalava (wrap arounds) and puletasi (women’s attire) for Samoa. Photo by Polynesian Cultural Center.

The team behind the costumes

Creating the costumes was a collaboration between a group of people. Allred said the role she played was drawing things because she’s not very familiar with traditional clothing.

“I’m Samoan but not familiar with other cultures. The way it happened was I sat down with Aunty Cathy, wardrobe supervisor of the Center, who has years of experience as a dancer and working in the wardrobe. We drew some stuff together then we showed it to our director, Ray Magalei, then he reached out to cultural specialists to get their input,” she said.

Allred emphasized the importance of involving cultural specialists to respect traditions and avoid mistakes. “For instance, we had a cultural issue with the Tonga men’s belt. Apparently, having diamonds on men’s belts is a no-no because diamonds are more associated with women. So, now we’re making rectangles to fix that,” she explained.

The collaboration added a genuine touch while deepening the team’s appreciation of different cultural aspects. By paying close attention to cultural details in the costume design, the final product was crafted to be both respectful and true to the cultures portrayed in the show.

Finished Hawaiian costumes for Huki. Photo by Polynesian Cultural Center.

Overcoming challenges in the preparation

Planning and preparing the Huki costumes required careful effort and attention to detail from the start. They aimed to distinguish this new show from the previous version of Huki but faced challenges in translating their overall vision into specific costume elements. Simplifying the show’s storyline took longer than expected, which led to the simultaneous development of a new track and the choreography of the dances. According to Allred, the extended planning phase caused costume considerations to be pushed to the last minute. Despite tight deadlines, the team impressively produced 300 individual costume pieces in just three weeks.

Allred said that under normal conditions, they would typically produce 100-150 items per month. Regardless of the intense pressure, the team’s dedication to quality and performance ensured that all the costumes met the high standards expected by their audience.

Elizza Keni, assistant seamstress supervisor from Australia, said, “You got to do what you got to do so the performers will look nice for the guests. The bottom line is the guests are paying so much money to come here and see a show, and they shouldn’t be looking at stuff that’s not good quality.

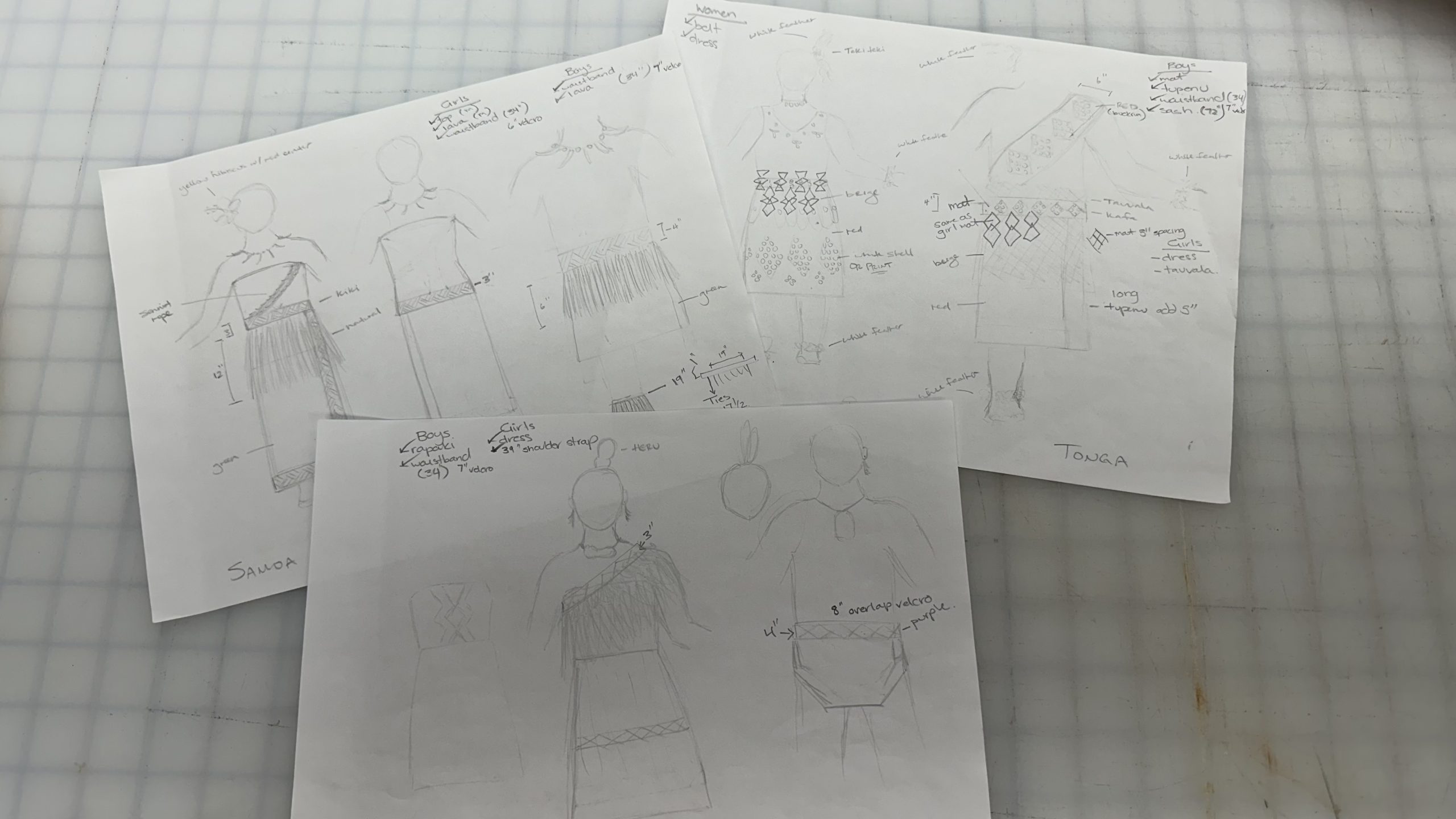

Some sketches of the costumes. Photo by Jesse Allred.

The rewarding experience of bringing Huki costumes to life

Each costume embodies not just fabric and thread but also the tradition and history of the performers’ background. Keni said, “In the sewing room, you see all the pieces but when you go out there, it makes you proud. It’s all worth it. I want to yell out there and say, ‘I made that!’”

Allred said, “It was cool when I saw some of the night show dancers model the costumes when I first went to the lagoon. It’s rewarding to see. I never grew up dancing, but when I watch Polynesians dance, I feel very connected to the culture of my family and ancestors. Even though I’m not a dancer, being able to make costumes and help people be part of that, share the culture and see them dance together is cool for me. One particularly touching moment for me was witnessing the joy and pride on the performers’ faces as they showcased their costumes during rehearsals. Additionally, seeing the performers’ connection to their cultural heritage through the costumes we created is incredibly fulfilling.

“Watching everyone come together, from seasoned seamstresses to eager student employees, is truly inspiring and highlights the collective effort involved in bringing the show to life,” Keni said. Allred added, “We’re grateful for our sister missionaries who volunteered. They come in and pretty much work full-time hours every day.”

Keni, who has been working in the Center for over 15 years, said, “Seeing the whole outfit complete is very rewarding. We wouldn’t have been able to do it without the help of our students and the senior missionaries. These are things that they’re not used to doing like putting clothing together and making dresses. It’s a bit out of their box, but they did it.”

We would like to express our gratitude to the seamstress and wardrobe department who truly demonstrated exceptional effort and creativity in the creation of the Huki costumes. Their dedication to craftsmanship and attention to cultural authenticity have greatly contributed to the overall success of the production.

Antoniette Caryl Yee-Liwanag, a Filipina, currently resides in the beautiful island of Oahu, Hawaii. She speaks Tagalog, Kapampangan, English, and Spanish, which helps her connect with people from various backgrounds while working at the Polynesian Cultural Center. Her blog explores exciting journeys of food, travel and culture. Though it may seem unusual, she enjoys the simple hobby of keeping her home spotless, reflecting her love for order and detail.

Antoniette Caryl Yee-Liwanag, a Filipina, currently resides in the beautiful island of Oahu, Hawaii. She speaks Tagalog, Kapampangan, English, and Spanish, which helps her connect with people from various backgrounds while working at the Polynesian Cultural Center. Her blog explores exciting journeys of food, travel and culture. Though it may seem unusual, she enjoys the simple hobby of keeping her home spotless, reflecting her love for order and detail.

Recent Comments