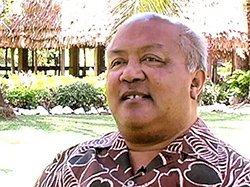

As the Polynesian Cultural Center prepares to celebrate its 24th annual Samoan World Fireknife Championship and We Are Samoa Festival on May 12-14, 2016, we turn to PCC retiree and High Talking Chief (an aloali’i of Manu’a) Galea’i “Pule” Pulefano for his historical insights on both the PCC’s special event and cultural origins of the popular ‘ailao afi’ or Samoan fire knife dance.

Note: In Samoan, the dance is called ‘ailao afi and the knife is a nifo oti or “deadly tooth.” Galea’i also holds his mother’s maternal family title of Va’aitautia in Aua, American Samoa.

The back-story

Following a major meltdown of the U.S. economy in the late 1980s, early ‘90s, the Polynesian Cultural Center management team was struggling to come up with ideas to counter the dramatic impact on Hawaii tourism, and consequently the PCC. Then PCC President Lester Moore suggested we stage something new, the introduction of special cultural events in addition to our regular offerings. Pule proposed the Center to host Samoan World Fireknife Championships.

Given his own background as a world champion knife dancer, musician, and entertainer with worldwide experience, he proposed that the PCC sponsor its first championships event in 1993; and he worked diligently each year to make sure that happened until he retired after 27 years in 2009 as the Center’s Director of Cultural Islands. As an example of his involvement, he personally made the over-sized ceremonial knife trophies for most of the first 20 years.

As with many success stories, however, this one began many years ago when Pule, who was born in Mapusaga, American Samoa, came to Laie at age 8: “My dad was already here attending Church College of Hawaii (renamed BYU–Hawaii in 1974), and he wanted our family to come and be sealed in the temple. That was in 1953-54. Laie became our home. We learned the knife dance, and we were among the first Samoans to participate in the Hukilau. We ran the pavilion there. I did the ‘umu [Samoan oven] and demonstrations, and helped my mom and dad with the shows when I was little.”

About five years later the Hawaiian Village Hotel (now the Hilton Hawaiian Village) in Waikiki hired Pule as “the youngest fire knife dancer in the world.” Soon, he and his brother, Prince Tafili, began performing every night throughout Waikiki.

At one time in his youth Pule and Prince won the first fire knife competition in Hawaii, sponsored by the Atoa O Ali’i Chief Council and the Royal Samoan Chief Council of Laie in 1964. He won his next fire knife competition in 1968, this one sponsored by the American Samoa Office of Tourism in Pago Pago; and he later represented American Samoa at the American Society of Travel Agents (ASTA) World Convention.

The Hawaii Visitors Bureau sent him on promotional tours to Japan, China, South America and the US mainland. “I remember those years: There was only a small group that went outside of Hawaii. No one else was promoting Hawaii at that time.”

He also appeared at the Hollywood Bowl and on the Ed Sullivan Show for the then-new PCC; and he did movies and TV work in Hollywood on shows such as Hawaiian Eye, Follow the Sun and Adventures in Paradise. Also, at one time he was the only fire knife dancer in the nationally televised, monthly Lucky Luck Luau. Then he and his brother formed their own group and toured the US and Canada. After a while, Pule split off with his own group and spent considerable time entertaining throughout Canada, and settling in New England.

“It was a beautiful life,” he said. “We trained over 100 young people in those years to become dancers and musicians.” But Pule eventually came home to Laie to help his aging mother. Of course, he soon formed a band that entertained throughout Oahu; and he accepted the job when the Polynesian Cultural Center hired him full time in 1982.

The championships and Samoan Festival

When the PCC approved his world championship proposal in ’93, Pule immediately began contacting every fire knife dancer he knew. “They came from all over the world that first year, because there was no other competition back then,” he said. “We were the first.” That first event was held in the Samoan Village, and PCC’s superb fire knife star then, chief Sielu Avea, won the first world championship.

To strengthen the PCC’s championships the following year, Pule worked with the late Obrien Eselu and merged his Hawaii Samoan high school cultural arts festival into the event that became the We Are Samoa festival. That name comes from the title of a popular song composed by Samoan artist Jerome Grey, who gave permission to the PCC to use it for the festival. To encourage their participation, Pule worked with the various high school Samoan and Polynesian clubs on Oahu, teaching and training them.

In 1995 girls were allowed to compete in the fireknife competition. Groups were added to the competition mix.

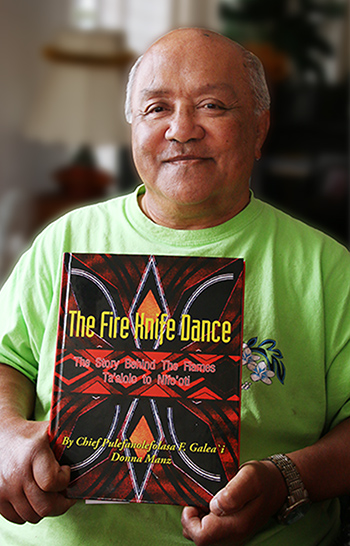

Pule’s book

Pule’s book

In 1994 Pule’s late wife, Susan, encouraged him to keep a record “of all that I was doing, for my kids.” He worked on it for the next 20 years, and recently self-published his own 185-page, heavily illustrated book, The Fire Knife Dance: The Story Behind the Flames, Ta’alolo to Nifo ‘Oti, by Chief Pulefanolefolasa F. Galea’i and Donna Manz.

“I wasn’t a good writer, but every night I would come home and write. That’s why I asked Donna Manz to help me with proper grammar and such, but I told her, you cannot change anything about the subject because she didn’t know the real meaning of the culture.” He then spent several years saving money to self-publish the book, even designing the tapa-motif cover; and he’s currently working on its distribution plans.

“I want people to know the origins of the ‘ailao afi,” he said, “including the strong cultural traditions and ceremonies associated with it from ancient days, and what they mean; and how the warriors would act and prepare themselves for battle.” For example, many of the traditional knife dance moves are associated with offensive and defensive actions ancient Samoan warriors would make in battle.”

“The dance only became entertainment in the last 60 or more years,” he continued. “The cultural background of the ‘ailao is very solid, but nobody fights anymore, so it’s now become very popular entertainment.”

What you may not know about Samoan knife dancing…

…from Pule’s book and comments he’s shared over the years:

“The ‘ailao was originally part of a victory celebration, that’s still enacted today as men twirl nifo ‘oti and other weapons during ceremonial ta’alolo,” Pule explained. “The ta’alolo is a traditional Samoan processional display of power, including singing, dancing, and the presentation of gifts that, anciently, would include the heads of defeated high chiefs. Completing the representation of force and victory, nothing was allowed to stand in the way of the victors, as sometimes even today participants strike at plants and trees along their path.”

“Old Samoan traditions say warriors would use the relatively lightweight nifo ‘oti like a hacking sword,” he continued, pointing out that some of these wooden swords or clubs had boar tusks or shark teeth attached. This weapon was eventually combined with the lave or hook, which was used to snare various body parts of an enemy, and looked more like today’s nifo oti..”

While Samoans sometimes joke about teaching their kids to play with fire and sharp knives, Pule notes that the dancers occasionally get burned and hurt; “and when they put the flaming knife on the soles of their feet, there’s no trick, other than developing thick calluses on their feet. Even so, those knives are very hot.”

While Samoans sometimes joke about teaching their kids to play with fire and sharp knives, Pule notes that the dancers occasionally get burned and hurt; “and when they put the flaming knife on the soles of their feet, there’s no trick, other than developing thick calluses on their feet. Even so, those knives are very hot.”

He explained fire became part of the Samoan knife dance when the late High Chief Letuli Olo Misilagi from Nu’uuli, American Samoa, was a young man performing in Hollywood in the late 1940s: “He said he was inspired by both a Hindu fire-eater and a baton twirler to add fire to his knives, increasing the level of courage and skill required to perform the already difficult knife dance.”

A few other facts

- Pule’s book mentions how to make and twirl 2, 3, and even 4 knives.

- Traditional ‘ailao movements include the mo’emo’e or running, indicating victory; foot stamping, a sign of challenge or intimidation; gego, or head moves to confuse the enemy; rolling the knife around the neck and through the legs to distract the enemy; and folifoli or movements leading up to a strike.

- Knife dancers today usually wear their lavalavas tucked up like a swimsuit, so there are no loose ends to get snagged. Adornments, such as shredded leaves, leis, headbands, arm bands and leg bands help accentuate movements.

- Anciently the ‘ailao was done to chants and songs. Today that role is taken by vigorous drumming that adds to the excitement. The compelling rhythmic beats come from traditional wooden gongs, bass drums and even metal cans and/or 55-gallon steel drums.

The future of Samoan knife dancing

In addition to many of today’s judges, over the years Pule has taught future knife dancers in Samoa, Tonga and the mainland, as well as his own nephew and son, David and Alex, both of whom have previously won the championship title. His younger relatives and neighbors can often be seen outside his house after school learning to twirl knives; and as this interview concluded, he was working with one of his relatives, a young girl, who was preparing to deliver the lauga or chiefly oratorical speech for Kahuku High in the upcoming Samoan Festival.

“I see knife dancing becoming more modernized, with a lot of creative ideas,” he said, “but I hope we never lose the traditional parts of the knife dance — the vigor and the energetic portrayal of warriors in battle.”

For more information, go to WorldFireKnife.com, call 800-367-7060 or 808-293-3333; it is recommended those interested in attending purchase their tickets in advance. Portions of the events will also be live-streamed over the internet at https://livestream.com/polynesia-live-event. For the 2016 schedule, go to http://www.worldfireknife.com/schedule/schedule.html

Story and photos (except where indicated) by Mike Foley, who has been a full-time freelance writer and digital media specialist since 2002. Prior to that, he had a long career in marketing communications, PR, journalism and university education. Foley learned to speak fluent Samoan as a Mormon missionary before moving to Laie in 1967 — and still does. He has traveled extensively over the years throughout Polynesia, other Pacific islands, and Asia. He is mostly retired now but continues to contribute to PCC and various other media.

Though Foley knew some of the Galea’i family in Laie, he first met Pulefano in the early 1970s in Pago Pago. He was still working fulltime for the Polynesian Cultural Center 26 years ago and became an original member of the committee when senior manager Pulefano Galea’i proposed starting the World Fireknife Championship event. He has since covered more than 20 of these past events.

Recent Comments