Tongan Lashing Expert

As contractors near completing the PCC’s newly renovated Tongan Village, a cultural expert in lalava or traditional sennit-cord lashing has been brought in to add some culturally distinctive finishing touches.

For the many centuries before Tongans and other Polynesians obtained metal from the outside world, they used miles and miles of sennit — kafa in Tongan, a strong flexible cordage created by braiding coconut-husk fibers together — to lash various parts of their wooden houses, canoes and other items together.

For the many centuries before Tongans and other Polynesians obtained metal from the outside world, they used miles and miles of sennit — kafa in Tongan, a strong flexible cordage created by braiding coconut-husk fibers together — to lash various parts of their wooden houses, canoes and other items together.

Thicker cords and ropes were created by braiding successively larger strands of kafa together, with some samples approaching the size of modern hawsers. Over time such lashings not only proved practical, but became artistic expressions with symbolic meanings.

Flash forward to today: As the number of traditional houses and canoes has diminished over the years, so has the need to braid significant amounts of kafa — which Samoans call ‘afa and Hawaiians call ‘aha — EXCEPT in some of the small islands in Fiji and the western Pacific. Likewise, the number of artisans practicing the ancient lashing skills has also declined dramatically.

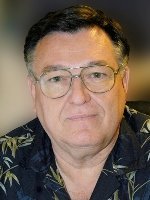

Enter Sopolemalama Filipe Tohi, a tufuga lalava or skilled Tongan artisan who now lives in Auckland, New Zealand: The Cultural Center contracted with Tohi to spend several weeks here lashing the new fale kautaha or meeting house, re-lashing several of the other buildings in the renovated Tongan Village, and also teaching some of the finer points of lalava to a few of our own people. Tohi was assisted by Su’a Sulu’ape Aisea Toetu’u.

Tohi has also done similar work in Samoa: In 2004 paramount Samoan chief Tupua Tamsese Tupuola Tufuga Efi — now Head of State — invited him to lash the fale maota at Nofooalii and train two others in the process. Tohi created the lashings for approximately 20 posts based on historic interaction between the Samoans and Tongans. In gratitude and respect at the building’s completion, they bestowed the Samoan chiefly title Sopolemalama on him, which roughly translates as “sharing the knowledge.” (Click here for more on Filipe Tohi’s artistry.)

“There are only a few Tongans who are capable of doing this,” said 77-year-old Tuione Pulotu, PCC’s consultant on the project: He first came from Tonga to Laie as a labor missionary to work on the Center and other projects, and has subsequently done numerous cultural construction project for over 50 years. We are lucky to get Filipe to come here,” he said.

Pulotu explained Tohi, who is originally from Nuku’alofa, Tonga, learned “from old folks, but most of it he developed himself” over the past 25 years. He added that kafa for the Tongan Village project came directly from the Lau Islands in Fiji: “Our first order was 6,000 yards, and we’re expecting another 6,000 to arrive,” he said, estimating the village will need about two-thirds of that to complete that project. That’s almost 5.7 miles of sennit, if stretched out straight.

A lot of kafa goes into creating the more ornate lashings. Tohi explained that’s because some of the logs being lashed are so big that it takes two guys to wrap the cord around and around. They also need scaffolding or a lift to work on the upper reaches of the buildings.

“In the old days the old people would sit down below and direct the workers on how to wrap the lashings,” Tohi said. “These days, it’s harder because no one understands, so I have to go up and get a lashing started, and then come down so I can more properly see the patterns emerge. When you’re closer, you can’t see that.”

“In the old days, the patterns helped tell a story, because our ancestors didn’t have written languages,” Tohi said. “Some of the patterns have names, such as manu lua — ‘two birds,’ and tokelau feletoa — ‘northern warriors.’”

Tohi also explained that in ancient times cleverly carved connections, wooden dowels and “basically lashings were the only thing holding building joints together.” He added that most such lashings, depending on the weather, could last the lifetime of the building.”

“I enjoy working and being here,” Tohi said. “We’re fortunate to have his help on this project,” Pulotu added.

Story by Mike Foley

Mike Foley, who has worked off-and-on

at the Polynesian Cultural Center since

1968, has been a full-time freelance

writer and digital media specialist since

2002, and had a long career in marketing

communications and PR before that. He

learned to speak fluent Samoan as a

Mormon missionary before moving to Laie

in 1967 — still does, and he has traveled

extensively over the years throughout

Polynesia and other Pacific islands. Foley

is mostly retired now, but continues to

contribute to various PCC and other media.

The traditional lashing of Tongan ‘fale’ is a closed art that belongs only to Tamale, the chief of Niutoua and therefore, the Master of ‘lalava’, or lashing. The art is still with Tamale,and lashings in Tonga of houses, like Tupou College, Sia’atoutai Theoogical College, the present king’s palace at Kolovai, the Weslyan church building at Pelehake village, the bildings at the Cultural Centre at Tofoa, etc. were under the direction of the late Tamale Pita. Now, is Tamale Mohenoa.