He stands on the deck of the wa ʻa, a Polynesian double-hulled sailing canoe, his eyes heavy from lack of sleep. He longs for rest, but his duty is clear: the navigator must be awake nearly all the hours of the sun’s cycle. There will be no time for long slumber until the vessel comes to land. For now, he squints at the dull light, diffused through dark clouds.

He tunes his mind to the rise and fall of the deck as ocean swells make contact with the canoe and pitch it up and down. The sea is rough, but not as rough as it might become, judging by the look of the sky. He feels the pattern. In this place—in open sea—he can rely on the consistency of the wind and the swells. The current flows from the east, driven by the winds. The swells hit the waʻa on its left outer hull—directly, straight on that side. The wind hits his body directly on the left as well. They are headed due south. At least their course has remained true through the night.

The navigator is pleased, and yet he cannot relax. The clouds of night hold trouble. The sun is breaking the horizon now, and the sky serves warning with brilliant red and orange. Knowing he will not have the clear companionship of the sun to help him wayfind as he would have hoped, he sifts his thoughts to access other tool he has honed throughout his life. His senses come to attention and his memory kicks into high gear.

Before the wa’a sailed, he mapped the course they would travel, but only in his mind. He knows the beginning. He knows the end. He knows the positions of the stars at this time of year. He knows the factors that will influence the currents. He knows the course they must keep to sail as straightly as possible from Hawaii to Tahiti. It is more than 2500 miles, and the lives of all on board are on his shoulders.

“Iosepa” by Debbi Weitzell.

The life of a wayfinder tends to be romanticized, but in fact, it can be grueling. Much responsibility and the keys to successful travel lie in the mind of one person. The explanation here will be a simple one by the standards of those who are skilled in this art. An article of this length could not begin to get into the intricacies that must be considered when plotting a sailing course. One modern-day navigator who has sailed using wayfinding methods on several waʻa over many years still considers himself a student of the complex array of patterns, conditions, and experiences. Maybe one lifetime is not enough for anyone to master the sea. Actually, anyone who thinks he has mastered it should probably stay at home.

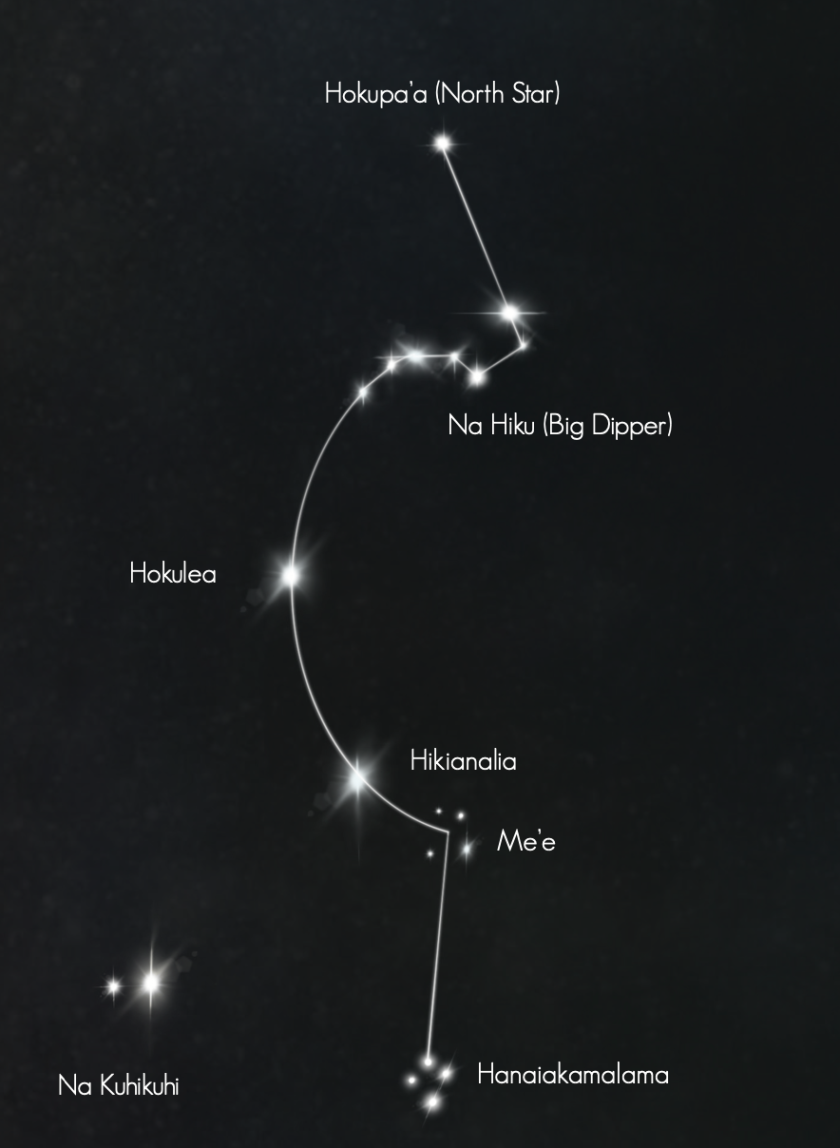

One view of the night sky.

There are many elements of wayfinding, developed in various places in the Pacific over generations.

Stars

Part of charting is knowing the constellations and major stars in the sky, and where they will be positioned at various times of the year. The positions of the sun and moon and their distance from the horizon also change with the seasons. This information is basic to understanding which direction the wa’a is traveling and to figuring out how to get to the desired destination. But that is only a small part of what goes into calculating and following a safe course.

Star charts can vary for at least two reasons: 1) navigators have individual sensitivities, and therefore create their own methods of expressing what they see in the sky; 2) though the stars always follow their given cycles, their positions may look different depending on where the navigator is observing them. See star charts here and here.

Swells

The story is told of a wayfinder who began sitting his grandson in the sea when he was a small child so that he would become accustomed to the rhythm of the water. High tide, low tide, windy conditions, stormy, calm seas, the pull of the moon (determined by the phase it is in)—he had to know them all, learning as their people had always learned. Each circumstance would be a big factor in how easy or hard a sail would be.

Variations in the movement of the sea is caused by swells. Swells are formed by the wind blowing over the surface of the ocean in connection with a severe storm. As the winds move away from the turbulent, deep water center, they carry energy that becomes waves—small and choppy at first, but gaining in organization and potentially in strength depending on how far they travel, and what obstacles they might encounter. Under the right conditions, this energy can manifest in organized waves, the size of which is also influenced by wind, the depth and contour of the ocean floor, etc.

Also involved here are the currents: the usual patterns of temperature and waterflow in various areas. In the open ocean, currents are usually fairly broad and predictable. But when a vessel enters the channels between islands, there are many intricacies affected by reefs, the ocean floor, and other structures as well as water temperature and the wind that can cause collisions of currents. The combination of factors can increase swells and change the course of the water. Sometimes those factors can combine to create some rough seas. Unless the wayfinder knows all the variations as old friends, she/he may be at their mercy.

This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-SA-NC

Clouds

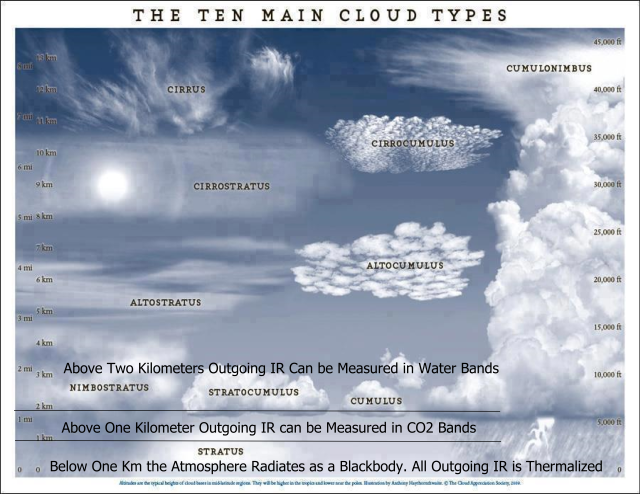

Clouds can, of course, be harbingers for coming storms; but they can have many other meanings. A simple explanation of the types of clouds we’re discussing follows.

- Light, fluffy cumulus clouds are relatively low in the sky and indicate fair weather.

- Middle altitude altostratus clouds are gray and are busy generating storms.

- Thinner, high-level cirrus clouds are generally light and wispy and are most known to cause interesting interplays with the sun or moon.

However, there are at least 10 variations of the basics, each with its own nuances. Those whose lives are tied to weather—whether they are farmers or sailors—learn read what is in the sky and predict what weather may be coming. For a wayfinder going to sea, this is crucial information.

Wind

Most people are at least somewhat aware of the roles of wind plays in weather. Wind temperature and speed are both indications of changes and causes of those changes. In the ocean, as calm winds caress the waters, sailing can be fairly smooth. A wayfinder would expect to see light, fluffy clouds and high, thin clouds on days like this. But the temperature changes, if darker clouds begin to form, winds may increase, warning the crew of storms ahead, but also making it harder to stay on course before the storm actually arrives—the swells, the currents, the clouds, and the wind combine to reflect the altering conditions.

Photo by Torsten Dettlaff on StockSnap

Birds

When sailing crews are at sea, the only other life around is in the sky and in the water. Because they are in their natural habitat, these creatures can be trusted to know what is happening, where shelter lies, and how to hunker down for foul weather.

Some birds are clear indicators of factors that may affect the sail. The seagull is a good example. First of all, if seagulls are present, land is not far away. And the directions that those birds are flying to and fro can indicate where the land mass is. Seagulls will also fly around an island or land mass as they go about their daily foraging, so a large congregation of land birds on a far horizon is a sure sign there is land in that direction.

If birds have been flying freely over calm seas and they disappear, that can be a sign that a storm is brewing. Birds can detect changes in barometric pressure and will usually take shelter before bad weather hits.

Seabirds like the albatross can be away from land for extended periods, so they don’t offer the same cues that land-based birds do. However, their behavior in storms can change as well. They may fly directly into the eye of a hurricane, or land on the water to avoid the strongest winds. Those who understand their behavior recognize these signs.

This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-SA

Marine Life

Like the birds, fish and sea mammals are very good at reading their environment. Strong winds, currents, and larger waves (which stir up sediment and reduce visibility in the water) send them looking for shelter. Small fish may hide in protected areas near shore. Larger fish and mammals may dive deep to avoid the tumult that is coming. When the threat is over, they will return to their usual pursuits. Just as with the birds, if a wayfinder notices a variation in the behavior of marine life, she/he can be sure that conditions are about to change.

These, then, are just some of the elements that a wayfinder has to keep in mind as the wa’a cuts through the water. The course must be firmly in memory before the canoe leaves shore, and yet the navigator must be ever vigilant, ready to modify the plan to meet the challenges Nature puts in its path.

Is Wayfinding a Romantic Pursuit?

Maybe. It does place the navigator on the ocean, sailing with salt air blowing through the hair and sun warming the face. It does require all the courage and confidence of a romantic hero. And she/he does have the responsibility for making a monumental event successful. But it is also serious business and extremely hard work that carries the very real possibility of catastrophic failure. Is that romantic? Perhaps it comes down to your definition of the word.

Recent Comments